Previous Subchapter → 9.4 Facts and Razors

But while we have instances of false negatives like the Mongush case, where claims of fakery are made without proof, we also have instances of false positives, where claims of a video being real footage from the frontlines don’t hold up to scrutiny, here’s an example of one:

Early into 2023, March specifically, a video emerged on Russian Telegram accounts seemingly showing Ukrainian troops committing a war crime, the video is a dashcam clip showing the view from a car, a Muslim family is shown being caught in a traffic stop by soldiers who appear to be from the Ukrainian military, with a giant Iron Cross and Ukrainian flag displayed on their vehicle, after the troops find out that the family are Russian speakers they quickly become aggressive, and when they move to leave the area they shoot at the car several times.

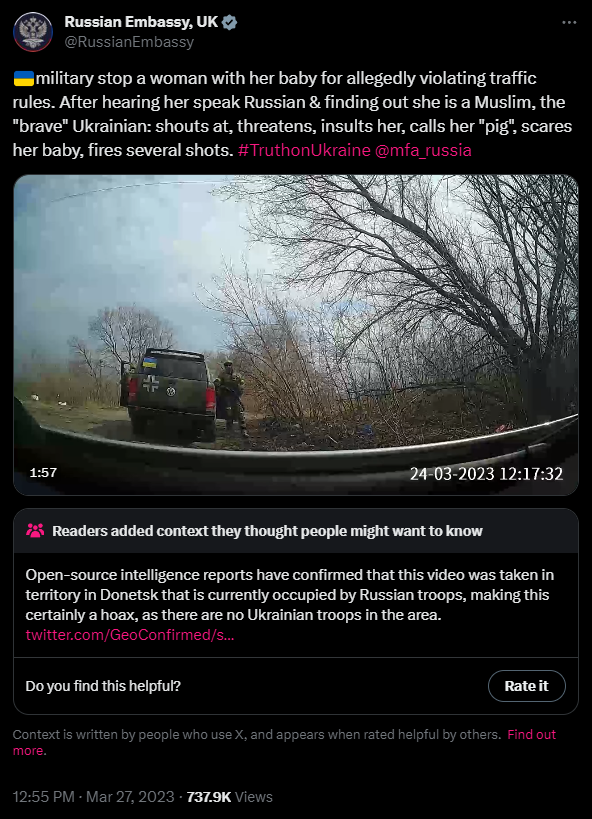

The clip was quickly circulated around by Pro-Russian outlets, including media organisations, other Telegram accounts, and even the Russian government’s UK embassy, and was used to amplify Pro-Russian narratives of a Ukraine invested by Nazi ideology:

“The ideology of the Nazi battalions in all military formations of Ukraine is extremely simple: one nation, one faith, one language. Everything is like the Third Reich, nothing new. Very suitable for limited enemy soldiers who have no idea that March 24 was the first day of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.”

- https://t.me/dva_majors/11800

As with the Mongush case, Bellingcat investigated the incident, but rather than supporting the claims, they disputed them, claiming that the video was a fake.

Unlike the counter narratives in the Mongush case, Bellingcat provided very credible evidence for their allegations, supported by various pieces of information, they noted that the footage had been geolocated by an outlet called GeoConfirmed, and that this outlet had revealed that the footage was over 30km deep into Russian controlled territory at the time it was apparently filmed, they also noted that the use of dashcam footage in Ukrainian controlled territory was highly unlikely, as dashcams had been banned in Ukraine ever since the early months of the invasion, back in 2022.

GeoConfirmed UKR.

— GeoConfirmed (@GeoConfirmed) March 27, 2023

"2 Ukrainians stopped a car and fires a gun to scare a women and child."

❌This is not Ukrainian military❌

This video is made 30 km's behind the frontline.

Russian disinformation, but geolocation by @PStyle0ne1 is on point and GeoConfirmed.

🧵👇

1/13 pic.twitter.com/gewMd6gImq

Location:

— GeoConfirmed (@GeoConfirmed) March 27, 2023

47.977044, 37.953754

XXG3+RG6 Makiivka, Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine

11/13 pic.twitter.com/3lbQUNMJF5

Some local Ukrainians went to the crossroad. https://t.co/IXNUmK6B6C

— GeoConfirmed (@GeoConfirmed) March 27, 2023

Says enough.

17/x pic.twitter.com/7O7FxdXWRA

And Bellingcat’s case was evidently correct, because even staunchly Pro-Russian outlets ended up admitting that the video was a hoax: Rybar for example, which initially used the footage to push their rhetoric that “Ukraine and Russia can’t peacefully exist” and “Ukrainian statehood should be destroyed”, later attached a correction admitting the video was faked. However, the Russian embassy kept their post up even after it was exposed, but thankfully a Community Note was added to correct the record.

So, what should the takeaway be from these two examples? Well, whenever you see a politicised or extreme claim, try not to make assumptions, look at each allegation case by case and search for context that either supports or discredits the footage. In scenarios like military conflicts, where every basic detail has become a flashpoint in the infowar, we cannot afford to give ground, do not take footage for granted, do not accept accusations blindly, no matter how reliable an aggregator may be, you should always look for the sourcing that backs their information up, this is why we work hard to rigorously source our work, we do not want to be taken at face value, we want our work to be trusted for one reason, and one reason only, we have the research to back it up.