Previous Subchapter → 8.3 The Invisible Filter

The need to combat dubious narratives and misinformation is a very real one, we strongly believe this, that’s what this whole episode is about, but that legitimate need is being exploited to enforce an unjustified level of control over society, the warning signs are right in front of us because we’ve seen this happen in Russia already.

Russia’s media regulator has justified the country’s censorship by claiming opposition media are perpetuating “false information”, the language of media literacy has been co-opted to enforce censorship.

And now the same process is used in Western Europe as well, with the EU leadership justifying the ban on RT and Sputnik by accusing them of “distortion of facts” “information manipulation” and “disinformation”.

Let us be clear, it is not the right of the government to tell us what is and is not a factual source, or to tell us we cannot watch certain news broadcasts or read certain news articles, for several reasons:

-

The first reason is a fairly obvious one, it’s completely ridiculous to trust an organisation like a government with regulating misinformation.

- A government cannot be a neutral arbiter on what is or is not misinformation, because every government has a vested interest in waging the information war in order to draw sympathy to its activities and maintain its influence, the conflict of interest is blatant, that applies to the Russian government, EU governments, every government, this is like trying to play a game of football with multiple referees who are all playing for the rival teams.

-

The second reason is somewhat more nuanced, even if an outlet is propagandistic it still has value, as we can learn what people on the other side of the world are hearing, denying ourselves the ability to analyse this is incredibly damaging for understanding complex issues like the Ukraine conflict.

- Because outlets like Russia Today clearly are propaganda outlets, essentially government mouthpieces, both because they have an instinctive bias towards the Russian perspective and because they are required to parrot state narratives by law, but that doesn’t mean we should refuse to read anything these outlets are publishing.

Like governments, search engine bosses are similarly being drawn into this conflict of interest as their leaders are allowing their political views to impact their service, and when you’re responsible for deciding what billions of people around the world get to see, that’s far too damaging to be acceptable.

When dealing with propaganda and biased reporting, the solution is not to try and block it out, but to encourage audiences to read with a pinch of salt, or maybe a whole table of it, healthy scepticism, this way we can both preserve free expression and fight misinformation, something the EU Commission claimed, but failed, to do with its regulations.

Because trying to block out “the other side” is just not going to work, restricting supply isn’t the same as restricting demand and if audiences still want to read these outlets they can, VPNs can easily be used to get around the website blocks of sites like RT and Sputnik, or even simpler, users can just paste the links for their webpages into the Wayback Machine and find archives of the whole sites to explore, these bans are only creating annoying inconveniences, not unscalable walls, so even if we set aside the fact that they’re wrong on principle, they don’t work in practice.

This Westward trend towards tougher internet regulation, represented by the EU’s media blocks and various other legal moves:

-

Like the USA’s RESTRICT Act (which intends to give the government the power to ban social media outlets from perceived enemies, like China’s TikTok, with very little evidence of harm needed)

-

Or the UK’s Online Safety Act, also known as the “Censors Charter” (which, among other things, aims to police how social media sites moderate so-called “legal but harmful” material)

Are a kind of attempt to “nationalise” the internet, similar to Roskomnadzor’s powers in Russia or the “Great Firewall of China”.

But you can’t “nationalise” the internet because the internet is by its nature international, there will always be loopholes for these kinds of blocks, this kind of censorship can always be dodged and these laws never actually erase the content they’re meant to.

The only way you could truly erase unwanted media or other content from the net would be to create a walled off version of the internet, an intranet, like the system that exists in North Korea, and that’s just impossible, not just because no one in the Western world would want that level of regulation in their lives, but also because it would be a practical nightmare to implement.

So the impact of these laws is that they give governments a concerning amount of power without actually delivering results. It sounds contradictory to say this is both dangerous and also unworkable, but that’s the reality.

These kinds of laws also lead to another kind of blowback, the Streisand Effect, it’s inevitable that if you block a publication, there will be a subset of people that will go out of their way to dodge the block and seek it out specifically because you didn’t want them to, the idea that an outlet is so concerning that the government wants to stop you reading it sparks curiosity, and curiosity sparks readership: What could they say that is so bad it has to be scrubbed from the internet? What is it that the government doesn’t want me to know?

This curiosity is something lots of outlets have exploited, in the West many conservatives exploited the rhetoric of cancel culture to great success, promoting themselves as the figures the establishment don’t want you to hear, conspiracy theorist Alex Jones probably took this strategy to its greatest extent by literally calling his platform “banned.video”, even though it’s a site you can freely access, it’s the perception of being a suppressed outlet that counts, and this is something RT has exploited too.

By making that censorship a real government policy, we’re only ensuring that supporters of these outlets will be entrenched, believing that they were on the right track all along, and these people will be placed in an echo chamber as outlets like RT and Sputnik are pushed underground instead of brought into the light and scrutinised, creating less trust, less understanding and more bias.

We need to avoid a segregated echo chamber internet, where east and west are living in completely different worlds blocked off from each other, and we in the West need to hear the other side of the story, because it’s an observable fact that media in Western countries is not “objective”, compare the reporting of outlets like BBC News on Ukraine from the first few years of the conflict to now and you’ll see a very clear difference:

During one recent news bulletin on BBC Radio 4, the correspondent referred to “Putin’s baseless claim that the Ukrainian state supports Nazis”. This is, itself, disinformation: it is an observable fact, which the BBC itself has previously reported on accurately and well, that the Ukrainian state has, since 2014, provided funding, weapons and other forms of support to extreme Right-wing militias, including neo-Nazi ones. This is not a new or controversial observation.

In 2014 the BBC was condemning the denialism and whitewashing surrounding the far-right in Ukraine, questioning why the Ukrainian public was not being informed about this issue,

“Ever since Ukraine’s February revolution, the Kremlin has characterised the new leaders in Kiev as a “fascist junta” made up of neo-Nazis and anti-Semites, set on persecuting, if not eradicating, the Russian-speaking population.

This is demonstrably false. […] But Ukrainian officials and many in the media err to the other extreme. They claim that Ukrainian politics are completely fascist-free. This, too, is plain wrong.

As a result, the question of the presence of the far-right in Ukraine remains a highly sensitive issue, one which top officials and the media shy away from. No-one wants to provide fuel to the Russian propaganda machine.”

This hyper-sensitivity and stonewalling were on full display after President Petro Poroshenko presented a Ukrainian passport to someone who, according to human rights activists, is a “Belarusian neo-Nazi”.

The Ukrainian leader handed out medals on 5 December to fighters who had tenaciously defended the main airport in the eastern region of Donetsk from being taken over by Russian-backed separatists.

Among the recipients was Serhiy Korotkykh, a Belarusian national, to whom Mr Poroshenko awarded Ukrainian citizenship, praising his “courageous and selfless service”.

The president’s website showed a photo of Mr Poroshenko patting the shoulder of the Belarusian, who was clad in military fatigues. […] And after the Unian news agency reported the presidential ceremony under the headline, “Poroshenko awarded Belarusian neo-Nazi with Ukrainian passport”, it was soon replaced with an article that air-brushed out the accusations of extremism.

Unian’s editors have declined to comment on the two pieces.”

There are significant risks to this silence. Experts say the Azov Battalion, which has been widely reported on in the West, has damaged Ukraine’s image and bolsters Russia’s information campaign.

And although Ukraine is emphatically not run by fascists, far-right extremists seem to be making inroads by other means, as in the country’s police department.

Ukraine’s public is grossly under-informed about this. The question is, why doesn’t anyone want to tell them?

and now since 2022 they are participating in that same denialism themselves, self censoring for the very same reason they identified in the past, a fear of emboldening Russian propaganda.

In 2018, The Guardian had published an article titled “Neo-Nazi Groups Recruit Britons to Fight in Ukraine,” in which the Azov Regiment was called “a notorious Ukrainian fascist militia.” Indeed, as late as November 2020, The Guardian was calling Azov a “neo-Nazi extremist movement.”

But by February 2023, The Guardian was assuring readers that Azov’s fighters “are now leading the defence of Mariupol, insisting they have shed their previous dubious politics and rapidly becoming Ukrainian heroes.” The campaign believed to have recruited British far-right activists was now a thing of the past.

Meanwhile, Germany’s state-owned Deutsche Welle required only three months after the invasion to pivot from calling Azov “a neo-Nazi volunteer regiment” to saying it was “accused of having [a] neo-Nazi past” by Russia. By this logic, the BBC’s and Deutsche Welle’s previous Azov coverage had been lies concocted by the Kremlin.

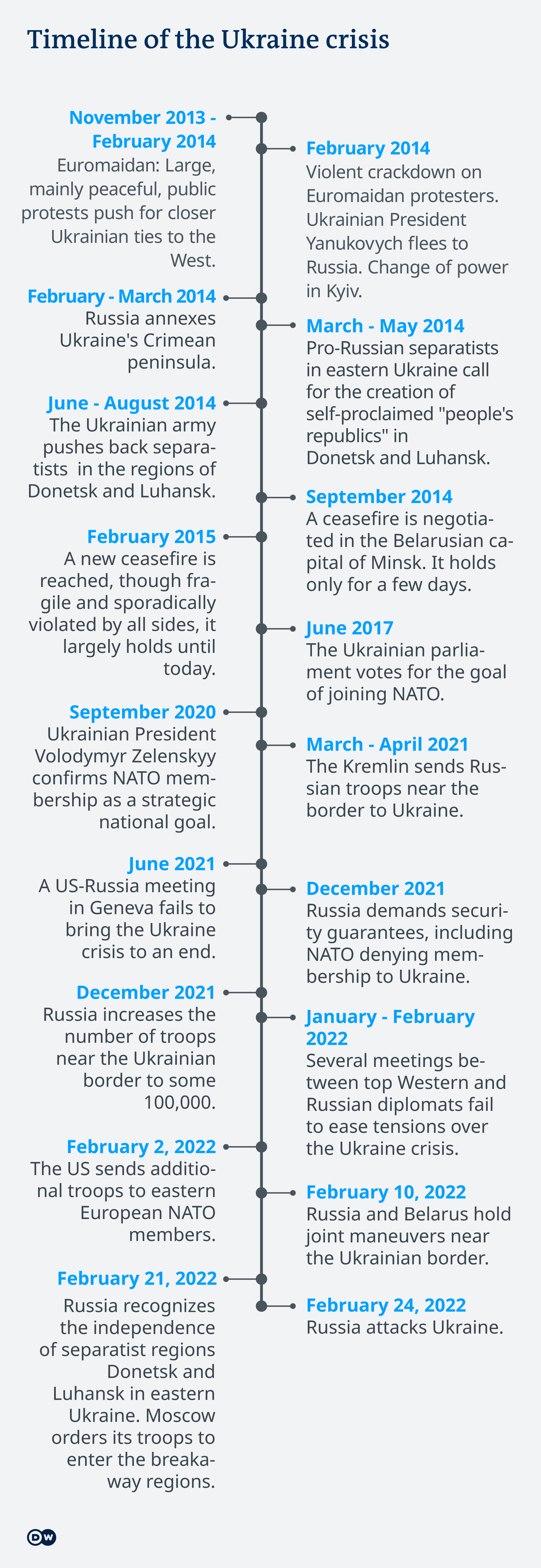

Even basic facts surrounding how the conflict unfolded have been rewritten, with descriptions of the Euromaidan referring to the events as a series of “mass rallies” or “mainly peaceful protests”, completely ignoring the paramilitary street wings of the “Maidan Self Defence Groups” which scuppered the deal between Yanukovych and the opposition.

Likewise, when the removal of Yanukovych by the Ukrainian parliament is mentioned, the details that this removal was unconstitutional, or that over 100 of his party’s MPs weren’t able to take part in the vote because the building had been seized by the Maidan groups, also go unmentioned.

We see this revisionism and selective reporting because there is a perception in the West that we are, on some level, at war with Russia, and in wartime the standards for truthfulness and objectivity are much lower, propaganda and obscuring inconvenient details are seen as more socially acceptable to maintain morale.

Before the 2022 invasion, topics like the constitutional questions surrounding Yanukovych, the leading presence of the far-right in the Euromaidan and their worrying influence in the aftermath, the Pro-Russia attitudes held in some of Ukraine’s East, Crimeans supporting Russian annexation, these were still talked about before without the need for hedging, scrutiny and questioning yes, but not hedging, now any sort of narrative that could make the conflict seem less black and white is either not discussed or buried in hedging to undermine the seriousness of that narrative.

That minimisation of nuance is ironically the exact same approach followed by outlets like RT, focusing 90% of the story on the preferred side, and maybe 10% or so on the counter narrative at the end, so it’s absurd that we’re banning Russian outlets for carrying out the same practices we do, just with the biases swapped the other way.

And we have to be conscious of just how dangerous this mentality is, because we are not at war with Russia, the war is a conflict between Russia and Ukraine, Western countries may be indirect participants, but this isn’t the same as the EU, UK or US having boots on the ground shooting Russian soldiers, or Russian bombs dropping on Western cities.

We shouldn’t just sleepwalk into the idea of suppressing freedom to protect freedom based on this wartime mentality, because we know what suppressing freedom to protect freedom looks like, it looks like the first Cold War;

A war that ended with a Western world that compromised over and over again on the values it was supposed to be protecting, sponsoring dictators and anti-democratic groups across the world, and denying the public the ability to understand the damage that was being done until it was too late.

Blocking one or two outlets like RT and Sputnik doesn’t seem so extreme and damaging on the surface, but the mentality behind these bans can lead us down a dangerous road, a road that has us laying the groundwork for conflicts like the War on Terror or the War in Ukraine without even realising it.

To be clear, these turns of events in the West, they are nowhere near as bad as what is happening in Russia, we could produce this documentary without being paranoid about forced “foreign agent” declarations, multi-year jail sentences or being blacklisted by government AI programs, and that tells you all you need to know about which media environment is healthier, but that doesn’t mean these trends at home aren’t a cause for concern, blocking publications robs us of our ability to independently cross reference the information we receive.

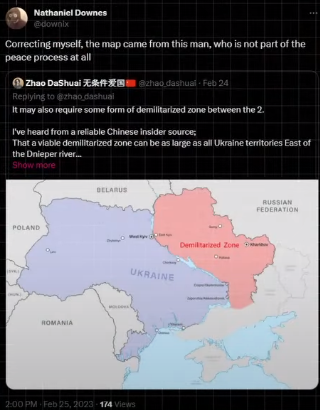

Let’s return to our case study: What if the page of this Twitter user, who posted their divided Ukraine map, was blocked? There could be a case for doing so, the user proclaimed this map as the “new map of Ukraine” and called their proposed settlement the “most realistic, least painful way to end the war”, we could interpret this as misinformation and remove it.

It may also require some form of demilitarized zone between the 2.

— Zhao DaShuai 东北进修🇨🇳 (@zhao_dashuai) February 24, 2023

I've heard from a reliable Chinese insider source;

That a viable demilitarized zone can be as large as all Ukraine territories East of the Dnieper river

Here's my take: pic.twitter.com/u7LVINkX7X

But in doing so, we would have no way of following the chain from the Quora post to the original source, and we would have no way of knowing whether or not the map really was from the Chinese state media, this could leave us with the impression that it really was a map from the Chinese state media, and by extension, the Chinese government, fooling us into buying a false narrative that China is seeking to divide Ukraine, in this example we can see that using bans to supposedly stop misinformation can actually allow it to spread uncontested, this is the kind of slippery slope media censorship can take us down. Limiting our ability to independently analyse media increases the risk of falsehoods being spread, and blocking Russian outlets robs us of the ability to scrutinise their claims ourselves.

https://twitter.com/downix/status/1629481345566257153

https://twitter.com/downix/status/1629481345566257153

So if we don’t use bans, how do we defend ourselves from the tight grip of fake news? Grassroots education on media literacy. As we mentioned, there are good resources out there already, but we need to go further, information on media literacy should become as widespread as possible, with the end goal of every user of the internet having an idea on how to spot misinformation, rather than only a select group of fact checkers and researchers.

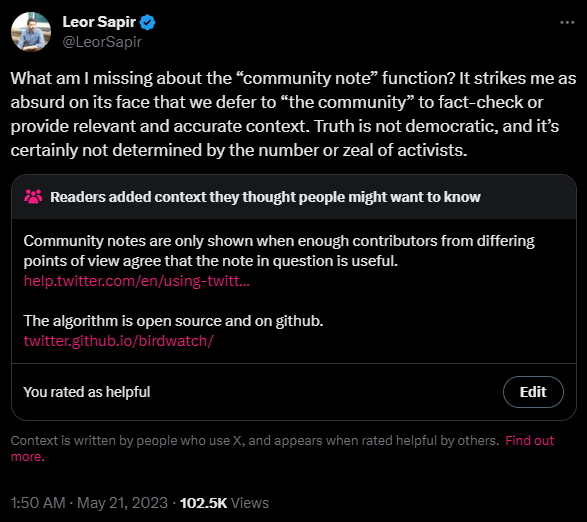

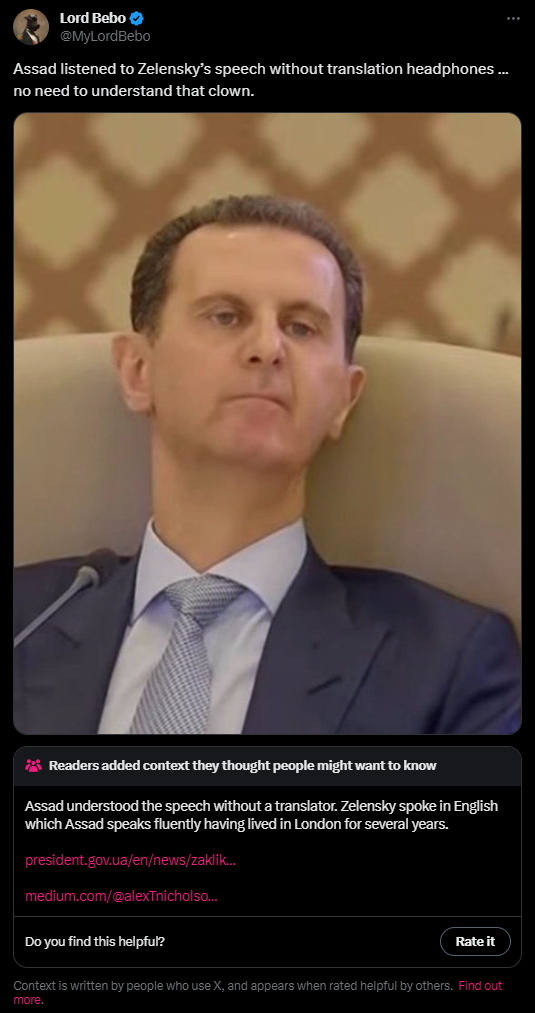

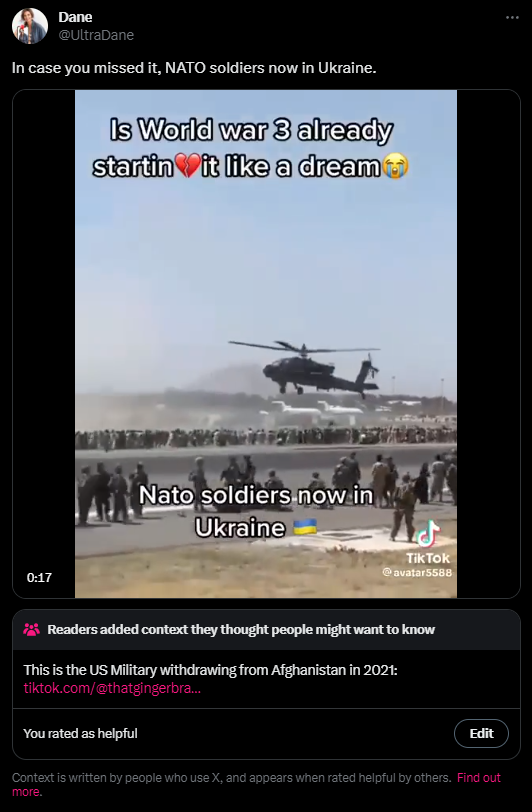

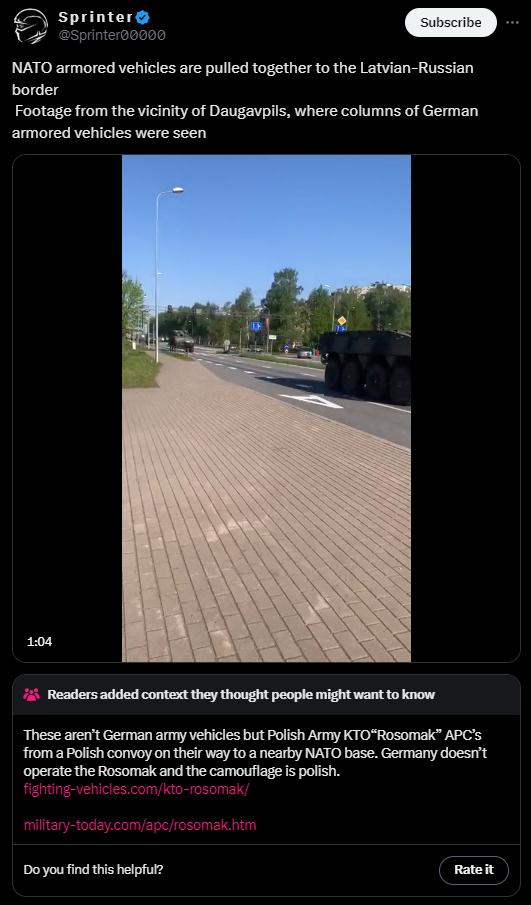

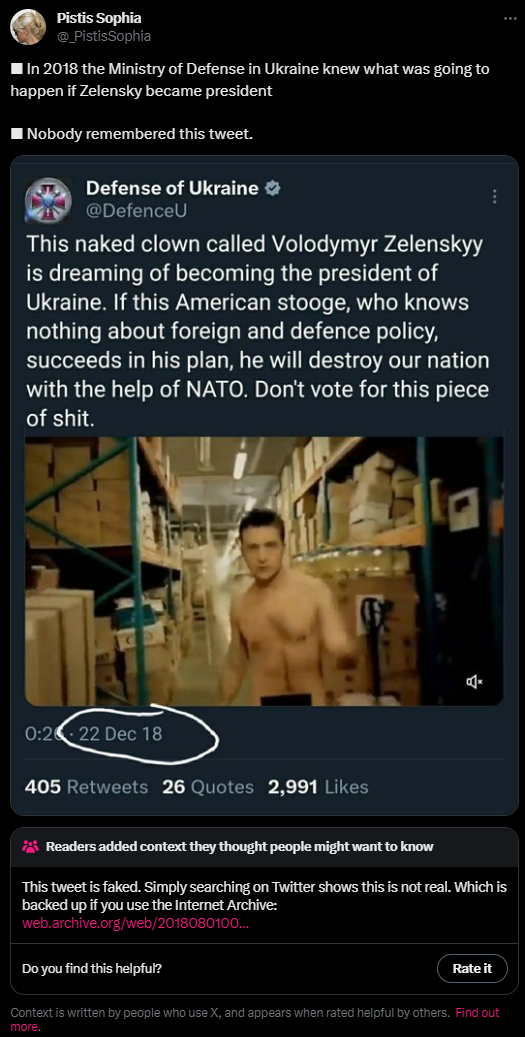

A great example of something like this in action is Twitter’s Community Notes system, where instead of unaccountable authority figures trying to hide misleading posts, community members can instead label them with extra context, with reliable labels appearing to all users based on ratings from the rest of the community and an open source algorithm, many of these notes are published all the time and they’re a much more trustworthy system for correcting the record than censorship, a system like this provides more information, rather than less.

https://twitter.com/MyLordBebo/status/1659572537200721923

https://twitter.com/MyLordBebo/status/1659572537200721923

https://twitter.com/UltraDane/status/1659312711338176513

https://twitter.com/UltraDane/status/1659312711338176513

https://twitter.com/Spriter99880/status/1657937979715846144

https://twitter.com/Spriter99880/status/1657937979715846144

https://twitter.com/_PistisSophia/status/1657905060569817088

https://twitter.com/_PistisSophia/status/1657905060569817088

With efforts like this, fighting misinformation can become commonplace in a healthy way, and that’s going to be more and more important as time goes on and the methods of misleading people get more sophisticated and widespread, these are major pitfalls on the internet that we all need to know how to navigate around, and educating people on them should be just as important as educating people about other risks like dodgy links and scammers.

And to help avoid these pitfalls, we have some advice of our own we can offer.