Previous Subchapter → Chapter 7 Summary

You are always just one tap or click away from accessing a whole new realm of information, which originates from beyond our countries borders. Some of this information is useful, a lot of it is not and a significant amount of data is manufactured, designed to mislead, uplift or beat down masses of people, depending on what that goal of the author is. These lies and half truths go by many names: Misinformation, disinformation, propaganda, “fake news” and “alternative facts” being just a few.

Fear or distrust of the media, and the risk of outlets spreading false narratives, is not new by any means, but in the last few years lies public consciousness on the topic of misinformation and the attempts to combat it through fact checking has catapulted into the mainstream.

A major catalyst for this was the 2016 election in the USA, an election marked by extreme polarisation, where the 2 key camps, Democrats and Republicans didn’t just have completely different views, but completely different sources of news, and the dispute over these sources is where the term “fake news” became popularised, amplified by Presidential candidate Donald Trump’s routine denunciations of the “fake news media”, denunciations that his supporters then adopted widespread, and this polarisation has only increased since then.

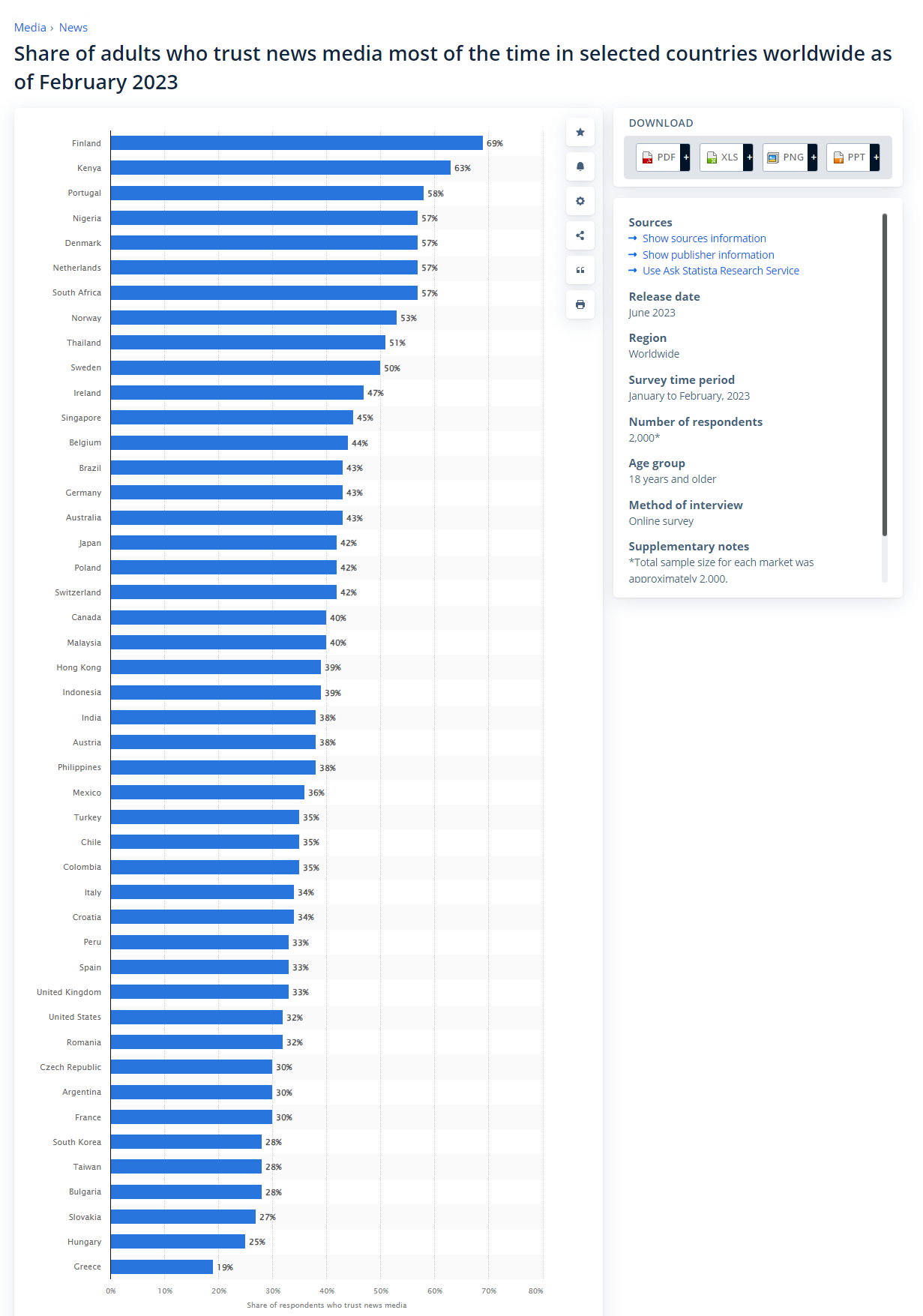

This isn’t just a US problem, it’s a worldwide one, trust in the media is at a dramatic low across much of the world.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/308468/importance-brand-journalist-creating-trust-news/

https://www.statista.com/statistics/308468/importance-brand-journalist-creating-trust-news/

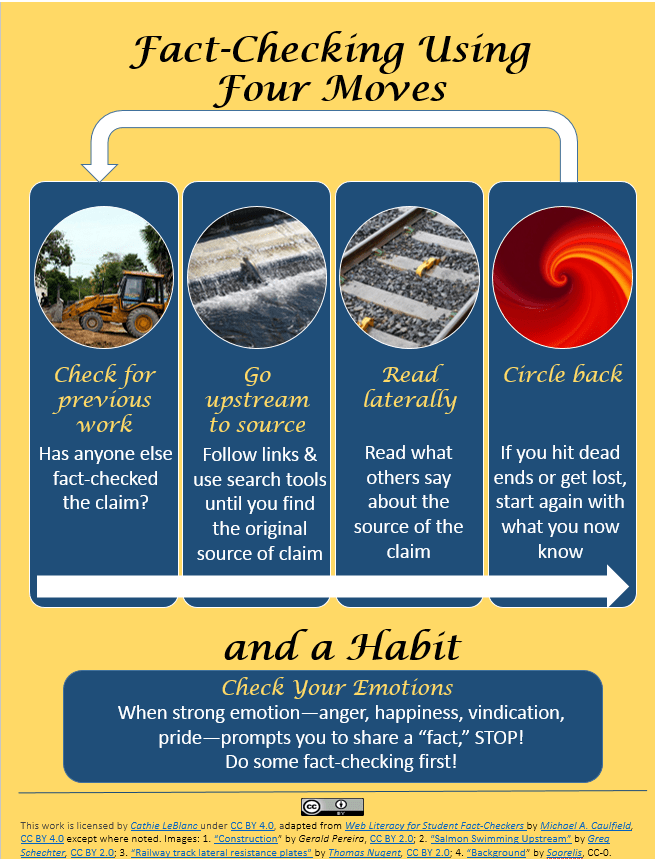

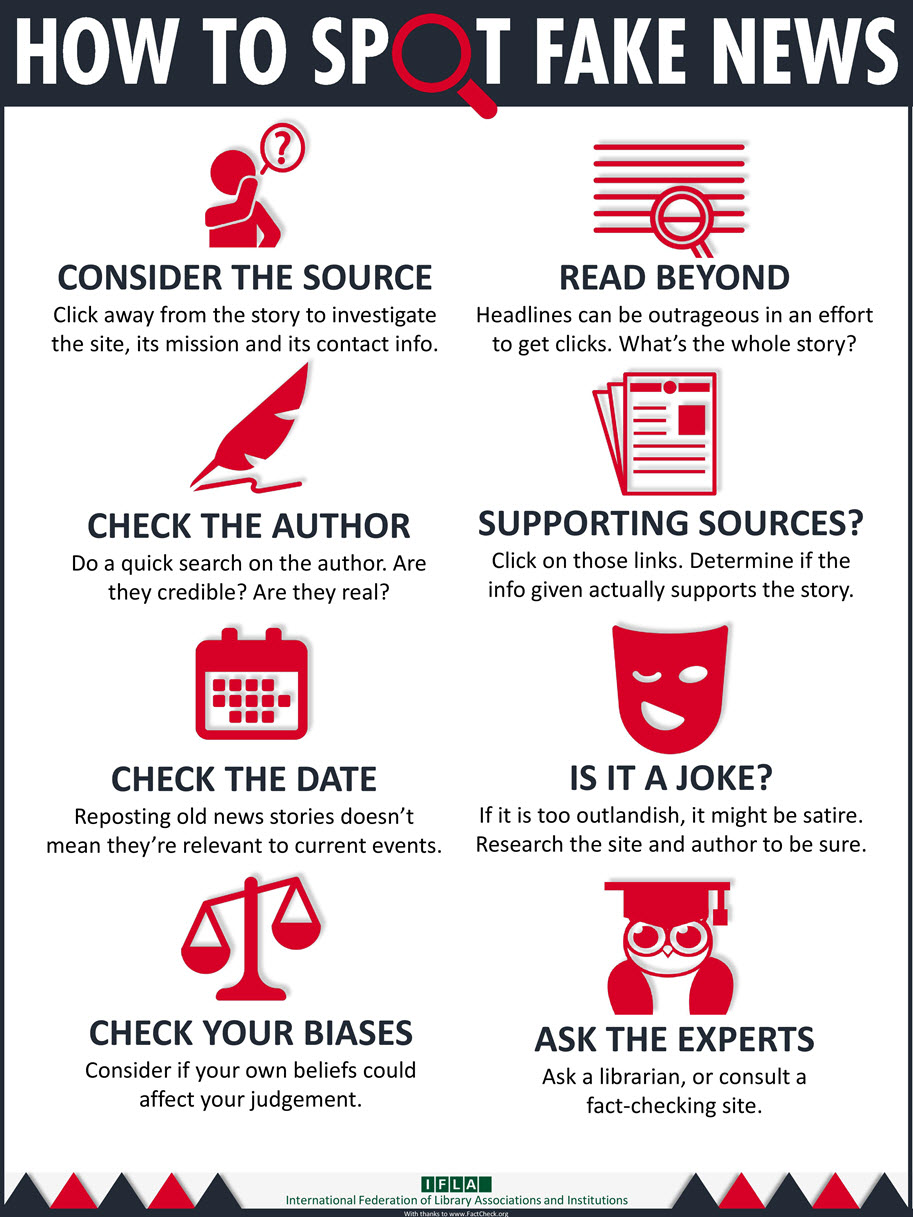

But believe it or not there is a positive side to this issue, attempts to promote media literacy are on the rise, rather than simply combating false narratives, resources are being published to show the public how to identify misinformation themselves: Sound advice like how to identify sources, consider the motives of publishers and the context surrounding the news we consume.

https://libguides.fau.edu/digital-media-literacy/evaluating-resources

https://libguides.fau.edu/digital-media-literacy/evaluating-resources

https://guides.library.cornell.edu/evaluate_news/infographic

https://guides.library.cornell.edu/evaluate_news/infographic

And this is a process we have participated in with the MEGA project too, with our Yeonmi and North Korea production we successfully pushed activist Yeonmi Park to take down misleading material about North Korea,

in our Ukraine Narratives production we gave a crash course on how context can be removed to paint a misleading picture of events,

and in this production, the Ukrainian Divide, we’ve taken that work further by unveiling more context and addressing misleading rhetoric.

Go back a decade or two and these kinds of productions would be all but impossible to make, so while the interconnectivity of the internet has allowed misleading agitators to spread their messaging further than ever before, it has also allowed honest analysts to do the same thing.

Let’s look at a small case study: This is a post from the social media site Quora, claiming that Chinese state media have proposed that Ukraine be subjected to a Cold War style division between East and West, it uses this map as proof.

Using Google Image search, we can find the earliest appearances of this map on the web, and it can be traced back to a Twitter post from a user called Zhao DaShuai, who takes credit for the map.

It may also require some form of demilitarized zone between the 2.

— Zhao DaShuai 东北进修🇨🇳 (@zhao_dashuai) February 24, 2023

I've heard from a reliable Chinese insider source;

That a viable demilitarized zone can be as large as all Ukraine territories East of the Dnieper river

Here's my take: pic.twitter.com/u7LVINkX7X

Since we were able to follow the chain back to the original source, we can tell that the claim in the Quora post is fake, this isn’t any sort of “state media” outlet, it’s a random blogger on Twitter.

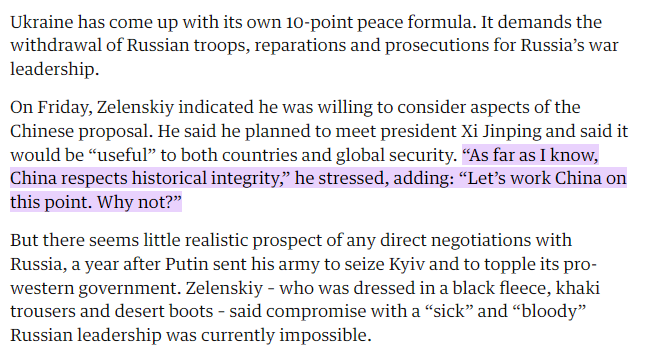

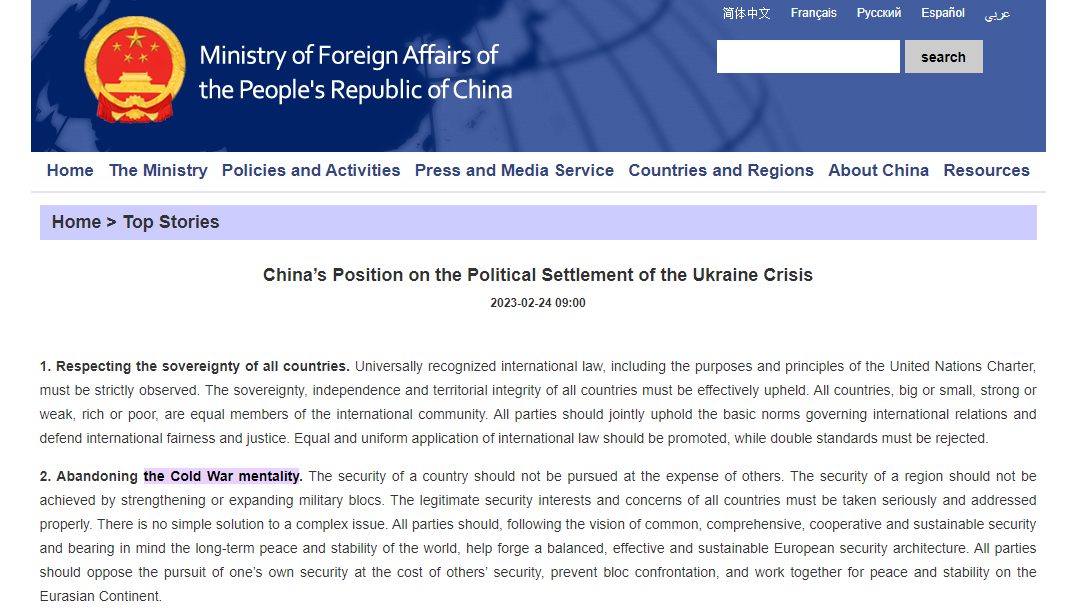

And if we look up China’s actual announcement of their Ukraine peace plan, it doesn’t include any sort of maps splitting Ukraine at all, it actually mentions the need to support “territorial integrity” for all countries, a fact that Ukraine’s President Zelensky noted shortly after the plan was announced, saying “China respects historical integrity, let’s work with China on this point, why not?”, the plan also specifically condemns the “cold war mentality”, further showing that the idea China is proposing a Cold War style division of Ukraine is nonsense.

In the pre-internet era of letters, books, word of mouth and newspapers, cross referencing like this was nearly impossible, and the ability for individual audience members to fact check the information they received was almost zero, you had nothing to go on beyond common knowledge, hunches or personal experience, the radio and television eras increased our reference points, with the ability for recordings to demonstrate happenings directly, but this era still left control over information in the hands of large organisations, the broadcasters.

Now, for the first time, sovereignty over information is in the hands of the audiences, you can evaluate the news for yourself, the tools are there to make this possible, that is unprecedented.

But the freedom provided by the internet is not a freedom we should take for granted, internet censorship is already a reality in most countries around the world, and most recently the invasion of Ukraine has exposed the cracks in this freedom.