Previous Subchapter → 7.3 Deaths in Data

To justify these genocide allegations, some analysts point to Russia’s use of dehumanising language regarding Ukraine, branding an unspecified amount of the population as either “Nazis” or “brainwashed by Nazism”, using derogatory language like “Ukrop” to refer to Ukrainian people, and then connect this rhetoric to war crimes allegations, painting an image of a holocaust style systematic incitement and practice of destruction, but this ignores the fact that unfortunately, dehumanisation is an often used tactic in war, for obvious reasons, it’s easier to kill an enemy soldier if he’s less of a person to you, an “other”, a chess piece on the board to be knocked over.

And this is a mentality the Ukrainians have incorporated as well, referring to Russians as “orcs” brainwashed by “Z mania”, we can look at other examples from this century as well, we have tended to compare the Russian invasion of Ukraine with the US invasion of Iraq, and we can see rhetorical parallels here as well, despite claims of “liberation” US politicians deliberately exploited imagery of terrorist attacks which Iraqis had no part in to define an unspecified amount of the Iraqi population as “terrorists” or “terrorist supporters”, demanding “De-Ba’athification” much as Russia now demands “De-Nazification”, the effect of historical distortions and vague charges like these is dehumanisation, and while the intention is to make it easier to fight war, it also for some makes it easier to commit or condone atrocities, when you paint a group, or an unspecified sect of a group as “the enemy”, it can promote an attitude that brutalising this group is in some way, acceptable, but despite this rhetoric, the occupation and the atrocities perpetrated against the Iraqi people, it would be sensationalistic and flat out wrong to claim Iraqis were subjected to genocide in this conflict.

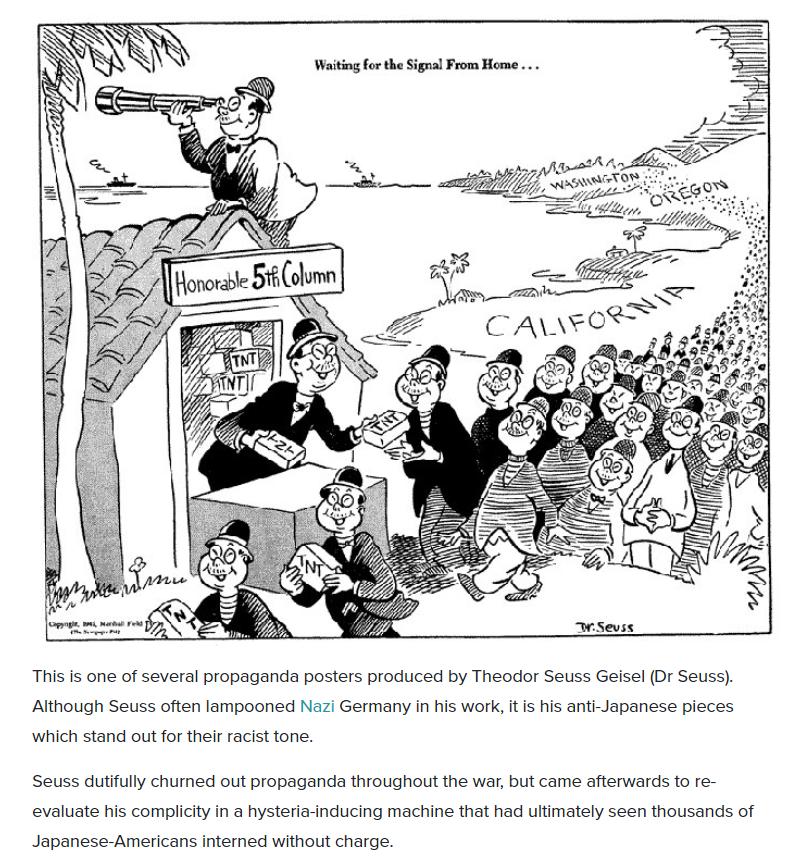

Additionally, outright racism is sometimes used as a dehumanising tactic to aid war morale, and there is a historical record of this, one of the most stark examples being the rhetoric towards the Japanese people during World War 2, who were referred to as “Japs”, made targets of caricature, isolation and ridicule, and placed in concentration camps because of a perception that an unspecified number of them were fascists, loyalists to the Japanese Empire, this rhetoric reached its maximum extent near the end of the war, when the Japanese people were warned that if they did not unconditionally surrender, “prompt and utter destruction” would follow. In spite of these practices, we rightly do not accuse the USA or the Allies as a whole of attempting to commit genocide against the Japanese people.

The point of showing these other case studies is not to excuse the use of dehumanising rhetoric, or to undermine the importance of analysing and condemning it, because as previously mentioned, dehumanisating rhetoric leads to atrocities, even if that isn’t its intention.

But the point is that racism, dehumanisation and cruel language, even though it enables cruel behaviour (especially in wartime) does not in itself indicate genocide, genocide is not just a charge of atrocities, it is the furthest an atrocity can go.