Previous Subchapter → 4.7 The Root Cause

But of course, it’s not just Ukraine that has this problem, there’s the other side of the coin we need to talk about, Russia’s Nazi problem.

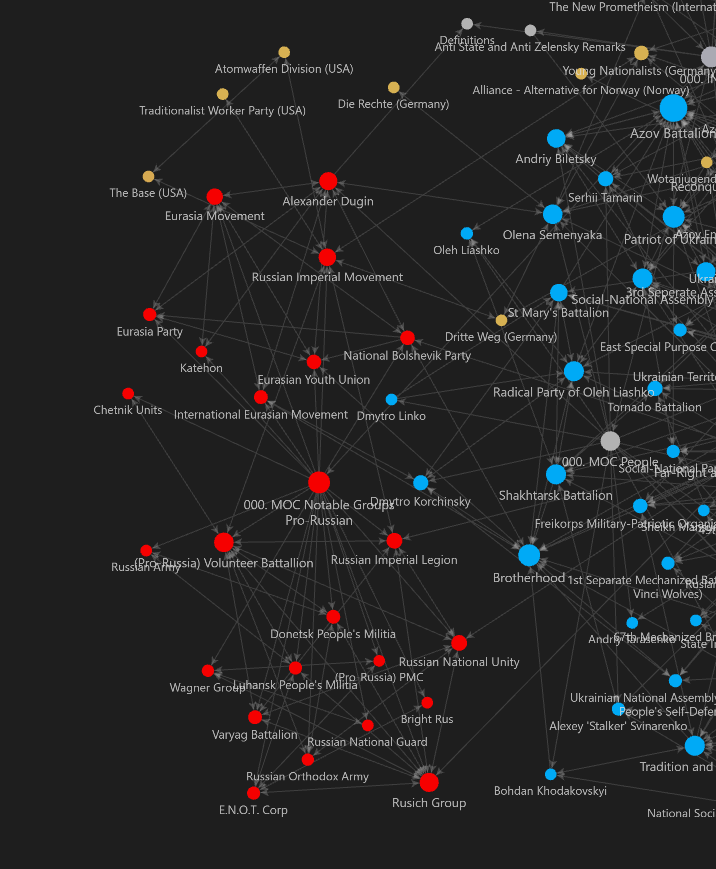

As we can see, there’s another part of this web of groups, and this is the one connected to the Pro-Russian and Pro-Separatist cause of the conflict, at a glance you can see that this network is much smaller than the network of Ukrainian groups, but looks can be deceiving.

While there are more groups that we know of on the Ukrainian side as opposed to the Russian one, the Ukrainian network is also bigger because it has been through more reorganisations.

If we think of the Azov Battalion for example it went from the Black Corps, to Azov Battalion, to Azov Brigade, and then the 4 Azov splinters, that’s 7 variants for just one organisation, which meant we had to spend 3 subchapters just explaining who they were, it was a similar story with Right Sector, with its web of coalition members and splinter groups.

What we found with the Russian groups is that this happens less often, the political groups and paramilitaries rebrand and split up with less frequency, meaning less data points on our graphic, but we still have quite a few figures and groups to get through.

To start, let’s open this with a question:

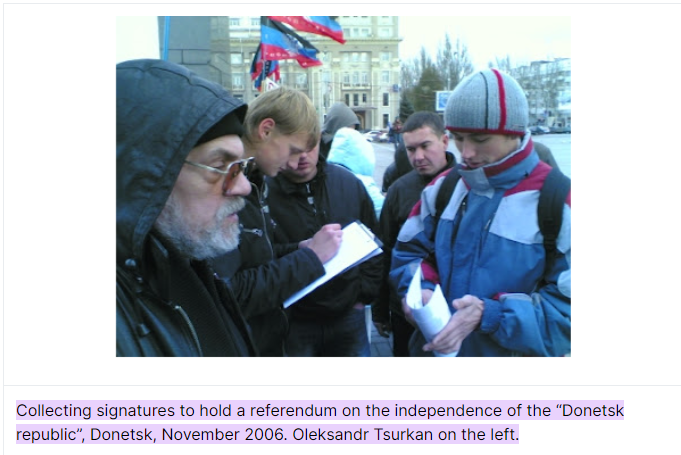

When do you think this picture was taken? It shows Donetsk separatist activists gathering signatures for a referendum, you’d probably say it was taken in 2014, right? Or maybe in 2022, after the Russian invasion?

Well, guesses like that would make sense, but they’d also be completely wrong.

This picture was taken all the way back in 2006, it turns out the separatist movement in Donbas goes back way further than most people know.

We found this image in an article by Euromaidan Press called “How Alexander Dugin’s Neo-Eurasianists geared up for the Russian-Ukrainian war”, the article details the beginnings of the Donetsk separatist groups, back when they were a weird fringe group that didn’t have any real power, but more interestingly it talks about the separatists early backing from a “Russian fascist” guru, Alexander Dugin.

Dugin believes in what we can only describe as the most schizophrenic ideology we’ll talk about in this episode, an ideology called, get ready for this, “National Bolshevism”.

National Bolshevism is essentially supposed to be a mix between Soviet Communism, Russian Traditionalism and Fascism, a mix that its followers show off proudly, with a seal that contains a mix of the Nazi Reichsadler, the Russian Empire’s coat of arms, and the Communist hammer and sickle, and a flag that takes the Nazi flag, rips out the Swastika, and replaces it with the hammer and sickle in the middle.

Even the greeting of the National Bolsheviks is a weird crossover between these identities, a raised arm Nazi salute but with the hand clenched into a fist in a style often used by Communists.

Now, if you know much about politics, you might be doing a double take at this and realising it makes absolutely no sense. The Soviet Union overthrew the Russian Empire, and marched into Berlin to destroy Nazi Germany, and on top of that Communism is a far-left ideology while Nazism, Fascism and Russian Imperialism are very much on the far-right, so how does this all mix?

Well, the answer is, Dugin just really really hates liberalism, he hates liberalism so much that he wants to find all of the ideologies against it, and bring them together to destroy the liberals. In most cases, this wouldn’t work, because if there’s one golden rule in politics, it’s that Communists and Fascists hate each other, but there’s a unique scenario where this unlikely alliance did actually happen, 1990s Russia.

This was at the height of the tug of war between Boris Yeltsin and his political rivals, Yeltsin was strongly backed by the West and despite his authoritarian methods he was essentially trying to introduce a liberal, Western style economy in Russia, this put him at odds with the Russian parliament, which at the time was filled with elected deputies from the Soviet era, mostly Communist Party members.

But the emerging Russian far-right also despised Yeltsin, while the Fascists and Traditionalists obviously didn’t have a lot of love for Communism, what they did admire was that the Soviet state was strong, powerful, and had a lot of influence over Russia’s former Empire and they saw that Yeltsin was dismantling this piece by piece.

As a result, Russia’s far-right and far-left in the 1990s had a mutual enemy, with the Black Yellow and White flag of the former Russian Empire often flying side by side with the red flag of the USSR in Anti-Yeltsin demonstrations, and it was this scenario that gave rise to “National Bolshevism”, or “NazBol” for short; Dugin later emphasised this sense of collaboration by taking on the slogan “beyond left and right but against the center”.

In 1993 Dugin founded the “NazBol” party alongside fellow Russian activist Eduard Limonov, and the party led demonstrations against Yeltsin’s establishment, calling for a restoration of Russian power and a renewed conflict with the Western world.

Within the “NazBol” ideology, Dugin introduced a geopolitical concept called “Neo-Eurasianism”, essentially the Russian version of the Intermarium, the concept called for Russia to go its own way, rejecting the West by forming a new alliance that would reach out to former nations of the Russian Empire and former countries from the Soviet Warsaw Pact, and then go further east, bringing together a huge bloc of Eastern European and Asian nations together against the liberal order.

But this partnership didn’t last, in 1998 Dugin and his followers left the NazBol Party, with the party accusing him of being a Fascist, and to be fair Dugin was hardly denying the accusations; In the year before his expulsion Dugin wrote an essay called “Fascism - Borderless and Red”, where he promoted “Fascist culture” and the totalitarian model, with a “god-like” “superhuman” leader, a Duce or a Führer, at the top.

Dugin’s pitch in this essay was that Russia had tried Communism, then Liberalism, and so the next step was Fascism, or what he called “Right-Fascism” and “National Capitalism”, the kind of Fascism seen in Italy and Germany.

But the promise he offered was that after this Fascist experiment, the new vision of what he calls “true Fascism” would emerge, where Fascist totalitarian culture and structures would be merged with the economics of “moderate socialism” to create “a new hierarchy, a new aristocracy” based on social justice, this is Dugin’s “Red Fascism”, which he considers “clean” and “ideal”.

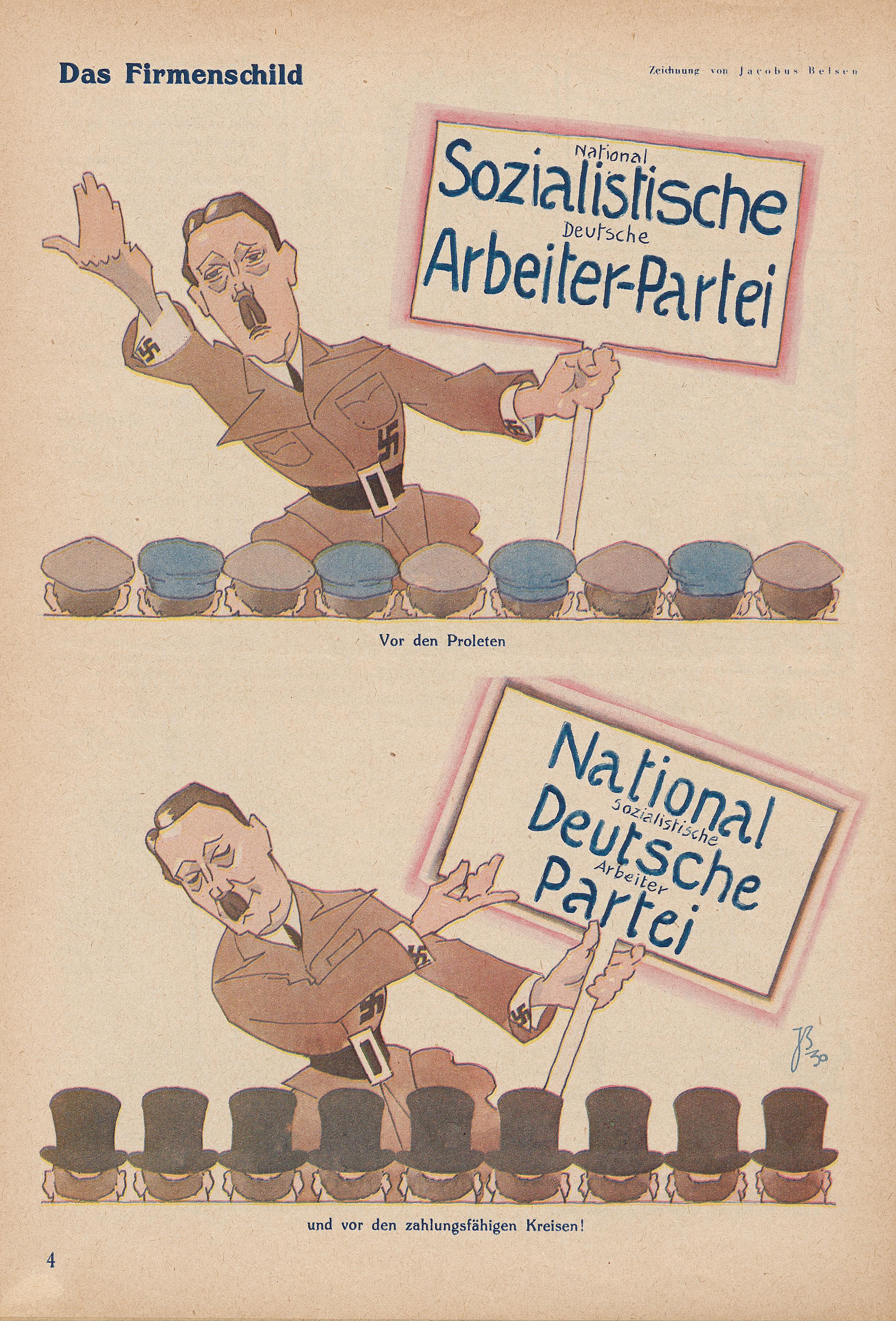

But of course, to many, Dugin’s promises of something new are simply a scam to mask his Fascist agenda, and it’s not hard to see why, the other leader who promised to blend his own idea of “socialism” with the Fascist model was none other than Hitler, after all “Nazi” does stand for “National Socialist”, but Hitler’s “socialism” turned out to be a con designed to lure working class voters towards the far-right, and many outside observers believe Dugin has the same idea, selling Fascist politics to Russia’s people by wrapping it up in nostalgia for the Soviet Union.

A parody of the Nazis from “The True Jacob”, a newspaper from the German Social Democratic Party

A parody of the Nazis from “The True Jacob”, a newspaper from the German Social Democratic Party

Whether or not you look at Dugin as a typical Neo-Nazi playing the optics game, like many of the other subjects we’ve covered in this episode, or you believe his claims to be building something more, what’s clear is that he stands for a totalitarian, regressive agenda, so he certainly deserves his spot on our list.

After Dugin’s movement and the NazBol Party split in the 1990s, the two groups went in different directions:

The NazBol Party continued their opposition to the Russian establishment when Vladimir Putin took power, and the party was banned in 2007, swapping it’s hammer and sickle for a hand grenade and reforming itself as “The Other Russia”, the party essentially moved towards a similar strategy as the Ukrainian far-right during the Euromaidan, joining hands with liberals to oppose their mutual enemy.

Dugin on the other hand decided to cosy up more with Russia’s new management, and in the early 2000s he formed the “Eurasia Party” and the “International Eurasian Movement”, these “Eurasian” activists were the people who formed ties with figures in Donbas, supporting the Donetsk separatist movement in its infancy. At this time the Duginites also cultivated ties with the Ukrainian far-right, including the Brotherhood Party, Ukrainian cells of the NazBol Party, and a familiar name, Olena Semenyaka.

With the breakout of the Donbas War Dugin of course threw his backing towards the separatists, seeing this as the conflict he had been wishing for, a Russian uprising against Westernisation, the NazBols also supported the dream of Russian conquest, with The Other Russia forming paramilitaries it called the “Interbrigades” to aid the Pro-Russian cause in Donbas; These events essentially killed off any idea of a Euromaidan style alliance between liberals and the far-right in Russia, as far-right activists moved towards supporting the war effort, placing their imperialist ideals above their opposition to Russia’s ruling oligarchy.

And the Eurasianists weren’t the only far-right groups involved in this early phase of the separatist movement, another key player was the “Russian National Unity” party, a Neo-Nazi party led by activist Alexander Barkashov. Early on in the conflict, Barkashov announced that Russian National Unity activists were involved in the fighting in Ukraine, and it also emerged that former Russian National Unity member Pavel Gubarev had become the leader of the entire separatist cause in Donetsk, declaring himself the region’s “people’s governor” and the commander of the Donetsk militia, something that Ukrainians happily pointed out to mock the Russian narrative that the separatists were “anti-fascists” resisting a supposed “Nazi regime”. Gubarev’s deputies also included members of Dugin’s Eurasia Movement.

Gubarev and Russian National Unity also controlled a Pro-Russian paramilitary called the “Russian Orthodox Army”, which later merged with the “Donesk People’s Militia” to become part of its “Oplot 5th Seperate Infantry Brigade”.

Gubarev’s relevance in the separatist movement later diminished, and he mostly stuck to activism, forming a movement called the “New Russia Party”, which later joined the second largest party in the Donetsk parliament, the “Free Donbas” party, but that wasn’t the end for far-right participation in the Pro-Russian cause.