Previous Subchapter → 4.3 The Azov Hydra

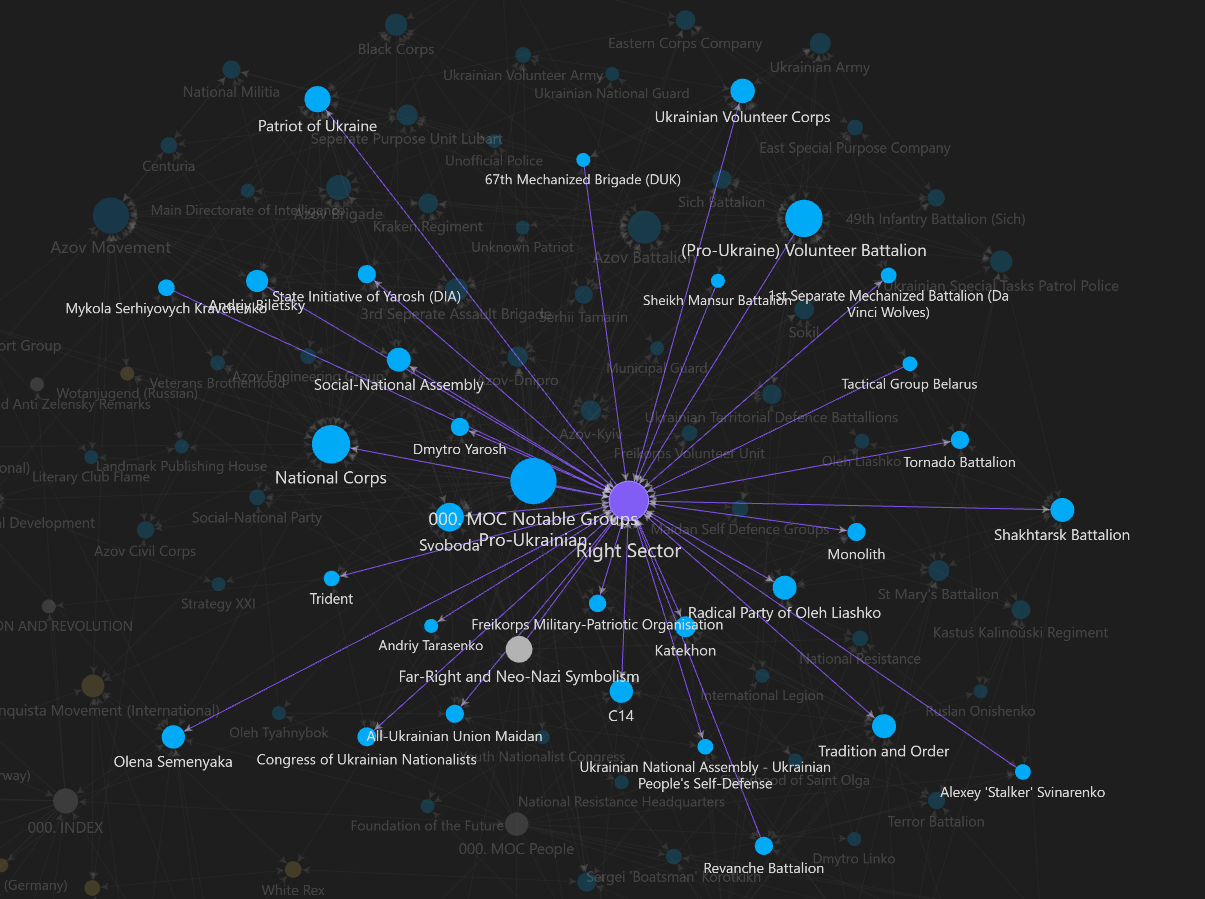

But while our first mistake was failing to realise the scale of Azov and its many branches, our second was hyperfocusing on Azov entirely, this is a mistake many outlets who dared to tackle the topic of the Ukrainian far-right have made over the years, developing a kind of Azov tunnel vision when there’s far more out there to cover.

Ironically, this is even a mistake made by Pro-Russian propagandists, who have the most to gain by drawing attention to this whole far-right umbrella, they often fixate on Azov and as a result, that’s where most of the narrative battles on this issue take place.

With the rushed production cycle of our original Ukraine Narratives documentary, where

writing and editing was done in roughly 2 weeks or less, we fell into this trap too, and we didn’t even come close to uncovering the big picture on this issue.

Of course, given the constrained time frame, we’re still proud of the nuanced presentation we produced, and of our deconstruction of the rapidly emerging propaganda narratives at the time, while many of our journalistic peers and even professionals who work for real news organisations didn’t really touch on the far right elements of this war, Russian or Ukrainian, we decided to talk about these uncomfortable truths we uncovered.

But nonetheless, we still made those mistakes, falling into the Azov tunnel vision and this time we’ve made sure we won’t make that mistake again, we’ve done our due diligence, it’s time we talked about the wider far-right umbrella that exists in the Ukraine conflict, outside the confines of the Azov network.

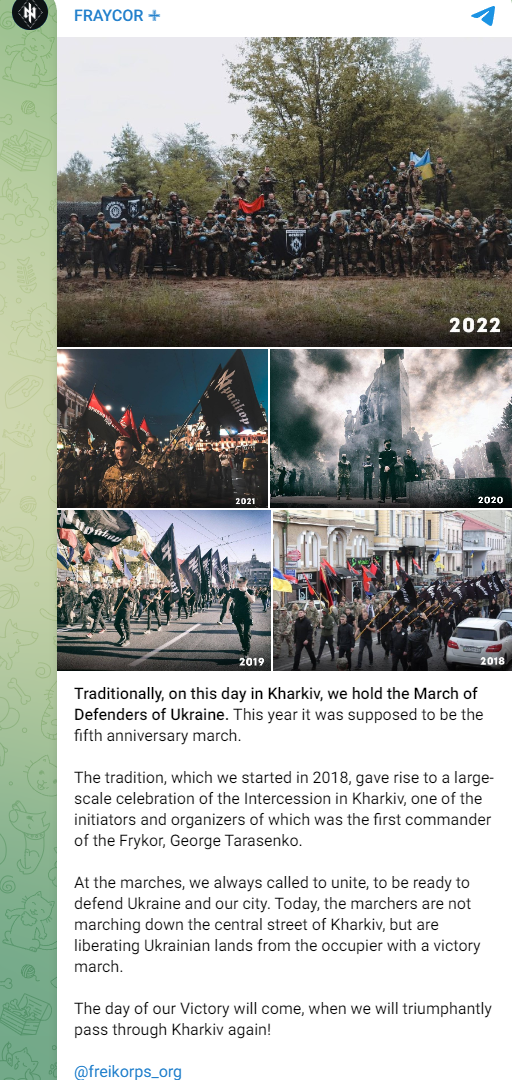

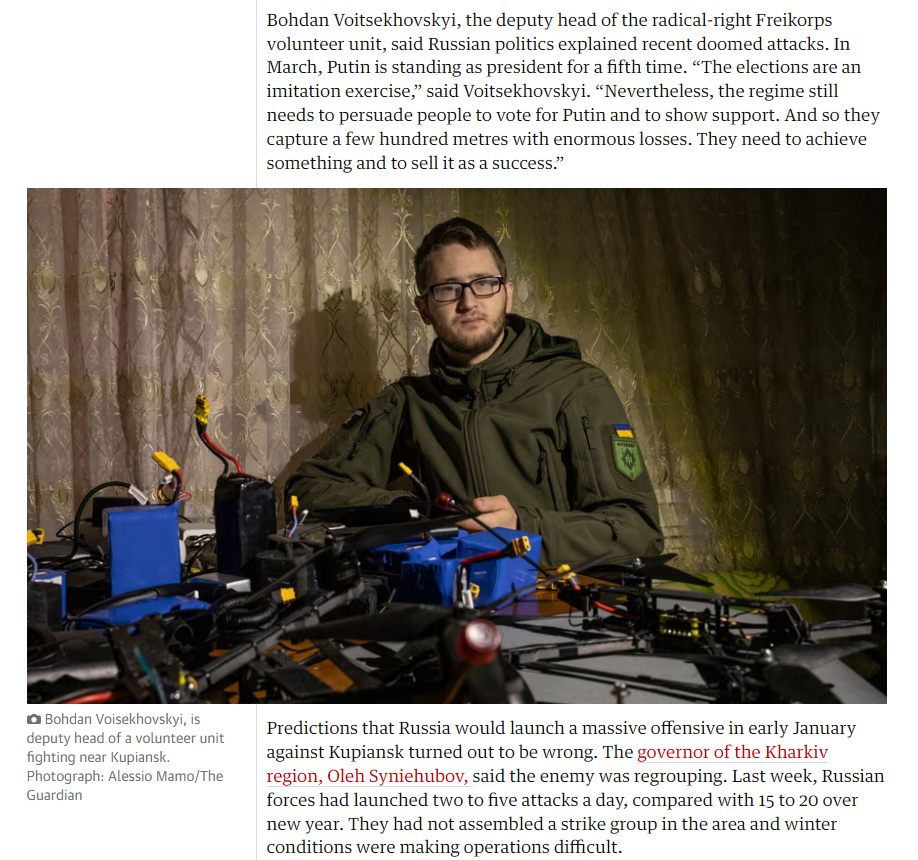

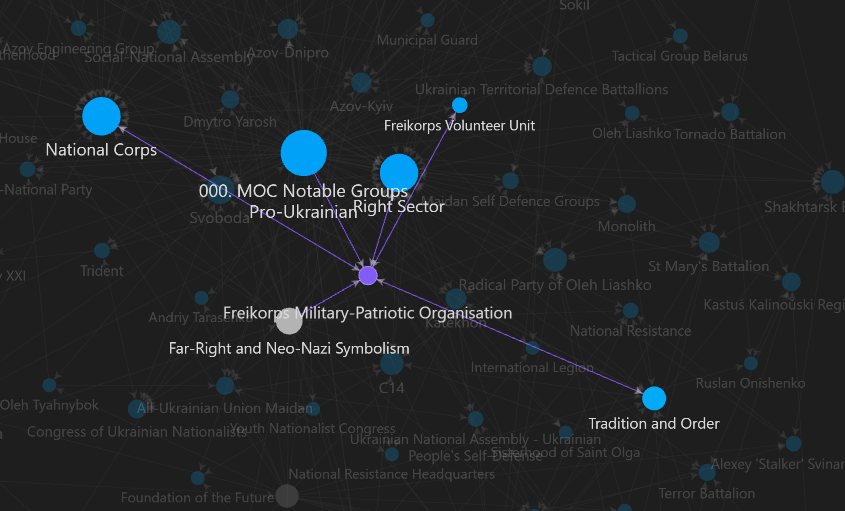

To start with, lets go only slightly outside the Azov border and look at the “Freikorps”, this is a group which has a military wing known as the “Freikorps Volunteer Unit” (formed in 2017) and a political wing called the “Freikorps Military-Patriotic Organisation” (formed in 2018), these groups were created by ex-National Corps affiliate Georgy Tarasenko and are dedicated to a variety of activities: Fighting on the front line, participating in political rallies, organising military training, and street vigilantism. Ideologically the apple doesn’t seem to fall far from the tree, Freikorps is happy to sport a stylised Wolfsangel (or “National Idea” if you prefer) and has participated in demos alongside various other far-right movements, more on some of them later.

A year later the invasion broke out and Tarasenko was killed early into the conflict, his organisation lives on however, and as of early 2024 the Volunteer Unit is still active in the Kharkiv region.

For their part the Freikorps refer to themselves as “National Conservatives” rather than Fascists, Nazis or “Social-Nationalists”, and they claim their name comes from older German Freikorps groups formed as far back as the 18th Century, rather than the Freikorps militias of the 1920s that went on to support the Nazis.

Those older Freikorps units definitely did exist in history, but that still doesn’t mean the Ukrainian Freikorps of today are harmless moderates, their social media posts can clue us into that.

The group has happily commemorated the SS Galicia Division as national heroes and celebrated the legacy of Stepan Bandera, and they’ve offered praise to various groups from the Ukrainian far-right such as the Brotherhood, UNA-UNSO, and the Ukrainian Volunteer Corps; Again, more on them later.

The Freikorps have also keenly offered their thesis on international politics, looking to the outbreak of the War on Terror as proof that liberal democracy has failed, having “degraded” and failed to “offer anything for human development”, what the group wants to replace it with they didn’t specify, but another post gives us a clue.

After the coalition withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 and the acceptance of Western nations that they would have to on some level talk with the Taliban, the Freikorps looked at the EU’s willingness to negotiate with a Totalitarian, Anti-LGBT, Anti-Feminist group as proof that the Western world would put pragmatism first and keep backing Ukraine even if nationalists came to power that would “hang these liberals on the Maidan”.

And although they’ve looked to less authoritarian figures like Hungary’s Viktor Orban and US Republican governor Glenn Youngkin as role models, they also commemorated Chilean military dictator Augusto Pinochet, who came to power by deposing an elected leftist leader and created a junta that would go on to organise Operation Condor, a massive, violent purge of leftist dissidents across South America.

So, just as with the National Corps, the Freikorps’ moderation is only skin deep.

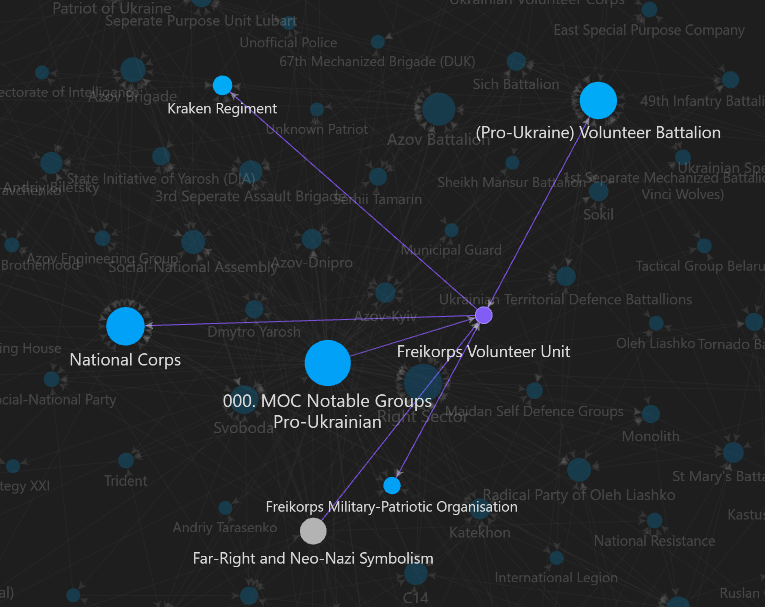

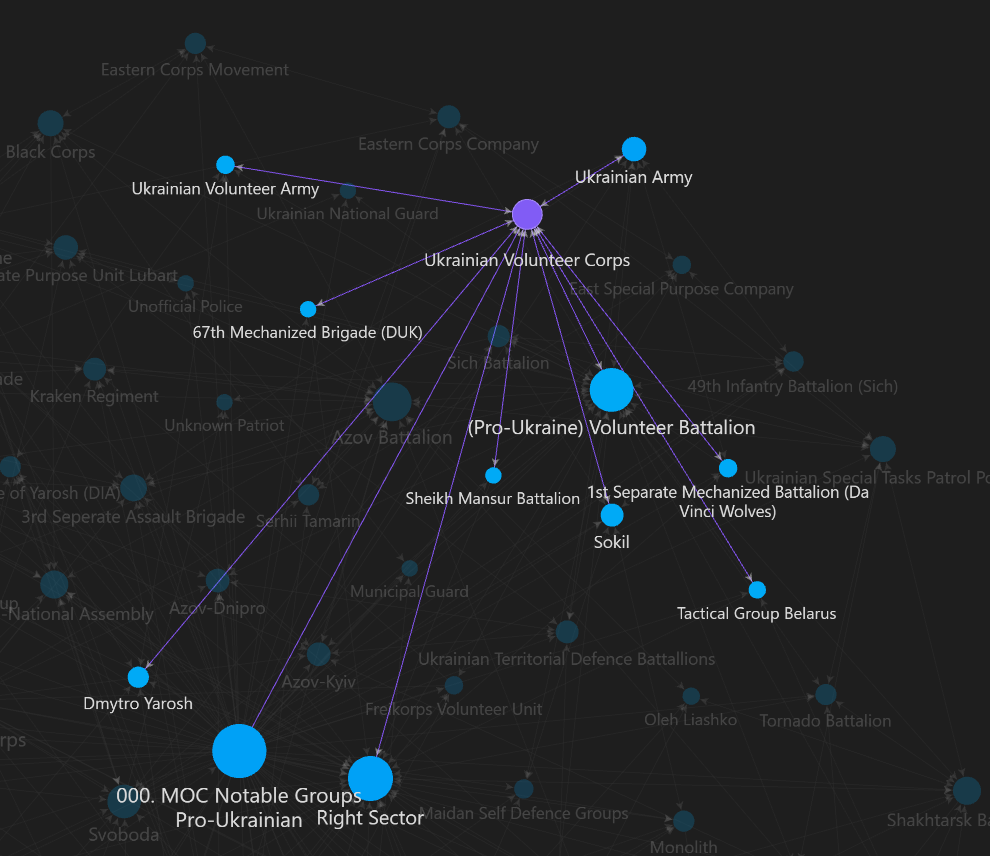

As for some of these other far-right groups totally outside Azov’s orbit, we talked about some of them already in the first episode of this series: How the Right Sector and Svoboda movements involved themselves in the Euromaidan protests and turned to paramilitarism with their so-called “Maidan Self-Defence Groups”, later converting to full blown military activity after the war in Donbas broke out, with Right Sector forming a unit called the “Ukrainian Volunteer Corps” and Svoboda forming a unit called the “Sich Battalion”.

And in order to explore the wider far right, it is worth looking into these groups in more detail.

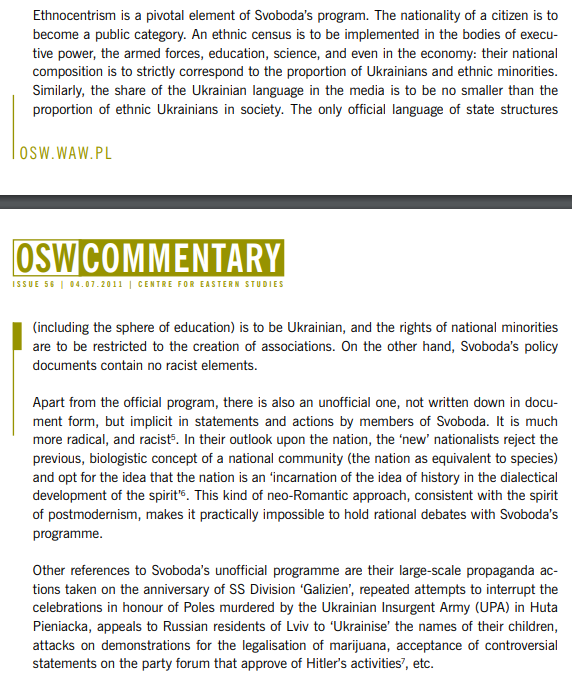

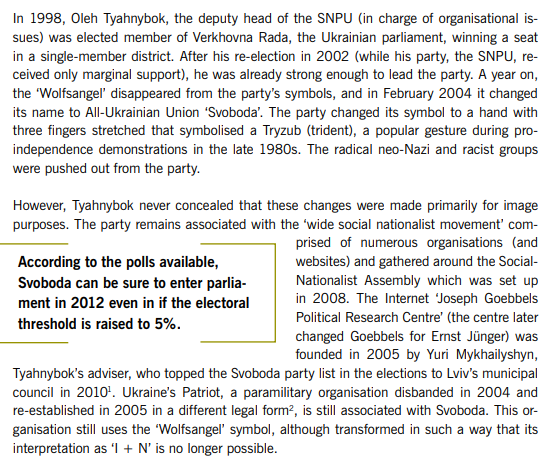

Svoboda we’ve already mentioned before; Alongside the National Corps they’re one of the heirs to the original Social-Nationalist Party, Svoboda is the wing of the party that tried to present a more moderate image, with its leader Oleh Tyahnybok ditching the Wolfsangel logo and replacing it with a 3 fingered salute, a stylised representation of Ukraine’s national emblem, the Trident.

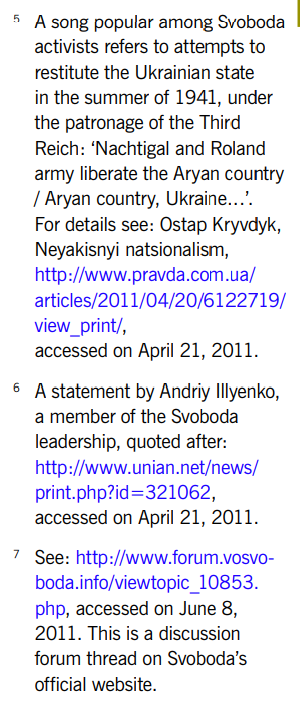

But according to the Centre for Eastern Studies, a Polish state backed think tank, Svoboda has closer ties to its original lineage than it likes to admit, with the party’s platform continuing to reference Ethno-Nationalism and its members continuing to commemorate the Nazis and their collaborators, in fact one of Tyahnybok’s advisors and top electoral candidates even went as far as founding a research group called the “Joseph Goebbels Political Research Centre”, which included translated articles from Nazi Party figures and even included a coded “Heil Hitler” in the domain name.

The BBC also picked up on Svoboda’s unconvincing reformism in 2012, a year before the events of the Euromaidan, contrasting Tyahnybok’s election season remarks about not being “against anyone” with remarks he’d made previously calling for Ukrainians to fight what he called the “criminal activities” of “organised Jewry”, and demanding a crackdown on a supposed “Muscovite-Jewish mafia”, despite being a supposedly reformist leader, Tyahnybok stood by his remarks when confronted on them by the Kyiv Post.

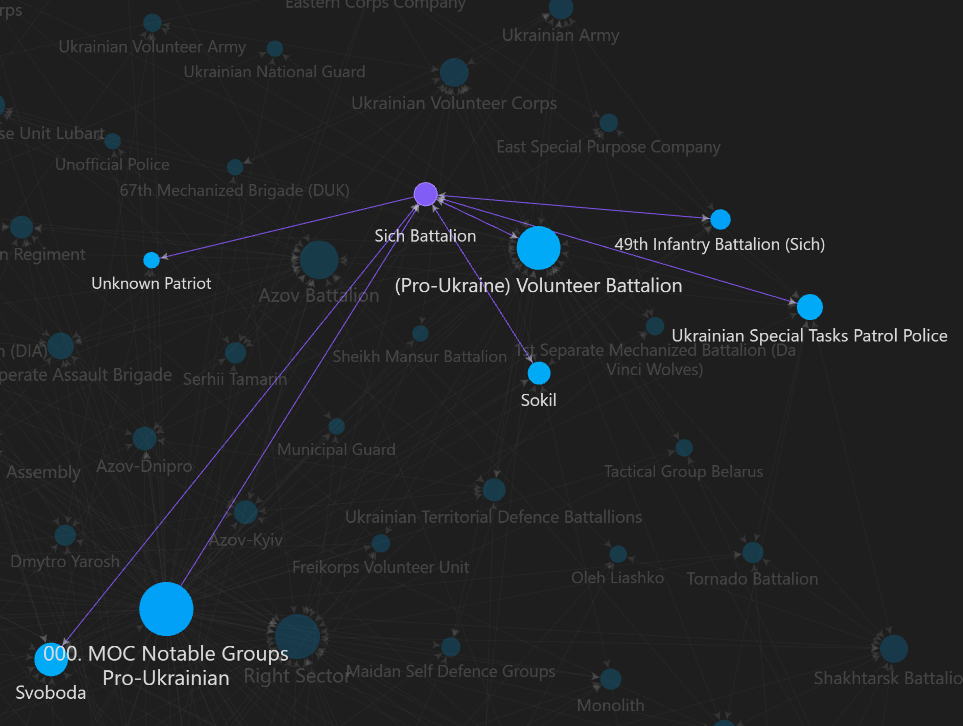

Now we’ve talked about Svoboda, we can tell you what happened to the volunteer unit they gave their backing to, the Sich Battalion. The Battalion was disbanded in 2016, only 2 years into the Donbas war, but like some of the other volunteer units they jumped back into action after the 2022 invasion, with the Battalion’s veterans coming out of retirement to reform the unit, it now continues to operate under the name of the “49th Infantry Battalion” of the Ukrainian Army. Svoboda’s continued patronage of Ukrainian units has caused further embarrassment for those trying to promote the ideas that Ukraine’s military is deradicalised and its Nazis don’t exist.

Interestingly, it seems that National Corps has taken some lessons from Svoboda’s playbook, although National Corps comes from the more uncompromising wing of the Social-Nationalist movement and, as we’ve seen, many of their branches and affiliates are very open about their Nazi views, the party itself has learned to play the optics game too, using their own stylised trident as their logo instead of the Wolfsangel and promoting a manifesto free of the blatantly Nazi platform promoted by the Social-National Assembly.

As for Right Sector, they have a more diverse origin. Right Sector itself was formed in 2013, bursting onto the scene with armoured thugs wielding red and black banners, baseball bats and shields being littered with Neo-Nazi iconography, ready to use violence wherever necessary. But the Right Sector isn’t really a single unit.

Similar to Azov today, Right Sector was (and still is) a conglomerate of groups, it included some names you’ve already heard of like Andriy Biletsky and the Patriot of Ukraine movement (which was a part of Right Sector until breaking off to form Azov), but also other movements in Ukraine’s far-right scene such as a group called “Ukrainian National Assembly - Ukrainian People’s Self-Defense”, formed as far back as 1990, and “Trident”, formed in 1993 as a subsidiary of the “Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists”, an OUN revival movement formed in 1992 which we mentioned in a previous chapter.

This cocktail of ultranationalist groups proved to be a powerful molotov, and as we described in the first chapter of this series, they were able to hijack what was originally a Pro-EU, fairly liberal protest movement, even while openly admitting that they didn’t care much for the EU or its liberal values at all.

The group also gathered quite a fanbase at the time, with Right Sector’s now blocked VKontakte page reaching up to 50,000 members, making it hard to estimate how many active members Right Sector really had. The organisation had humble beginnings, however as time showed, the group was not to be underestimated.

And like the Azovites, Right Sector also took on various foreign groups into its ranks as well, recruiting Chechen independence fighters known as the “Sheikh Mansur Battalion” and Belarussian fighters under the name of “Tactical Group Belarus”, into the Ukrainian Volunteer Corps.

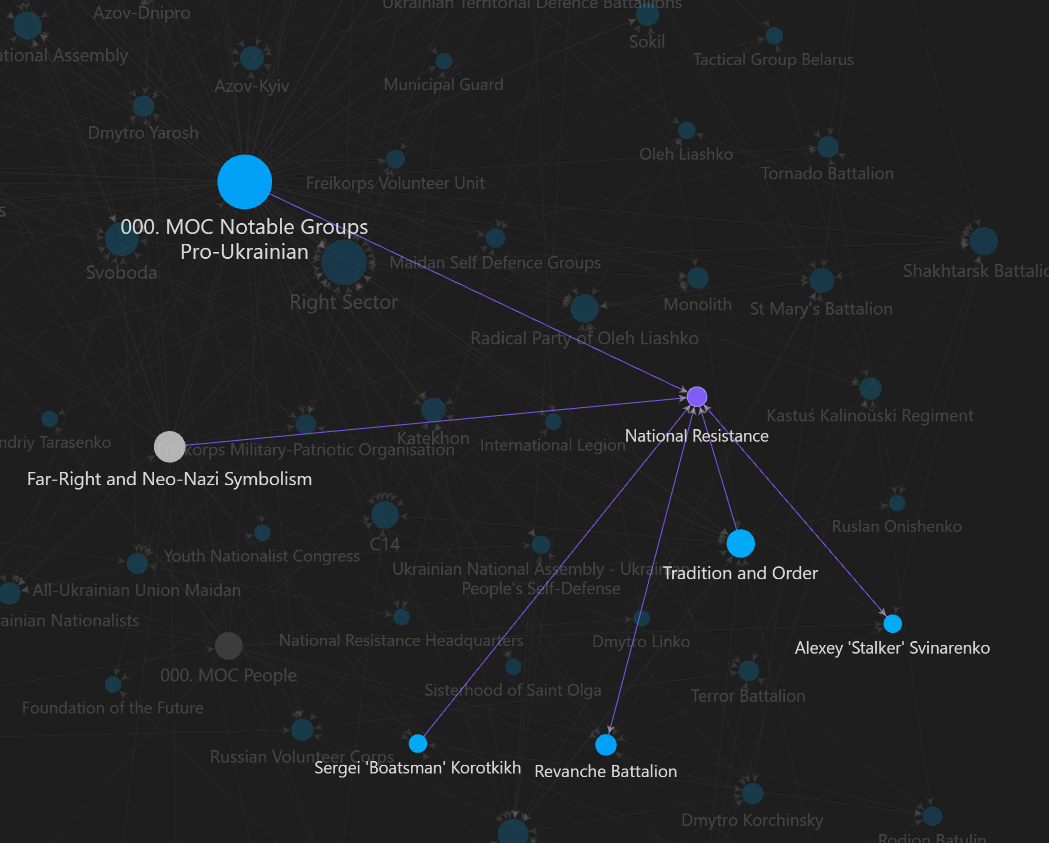

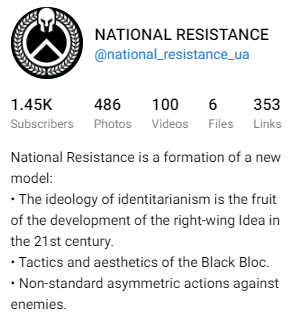

But due to Right Sector’s disjointed nature, it also ended up fathering various splinter organisations. Some of these organisations were smaller in size, such as the so-called “National Resistance” movement, a group led by former Right Sector activist Alexey Svinarenko.

In an interview, Svinarenko blasted Right Sector’s leadership as “too liberal”, holding back a strong activist base, attacking the coalition for being, as he put it, Jewish led and having a bulging nose, after leaving Right Sector he joined another far-right affiliated unit known as the Revanche Battalion.

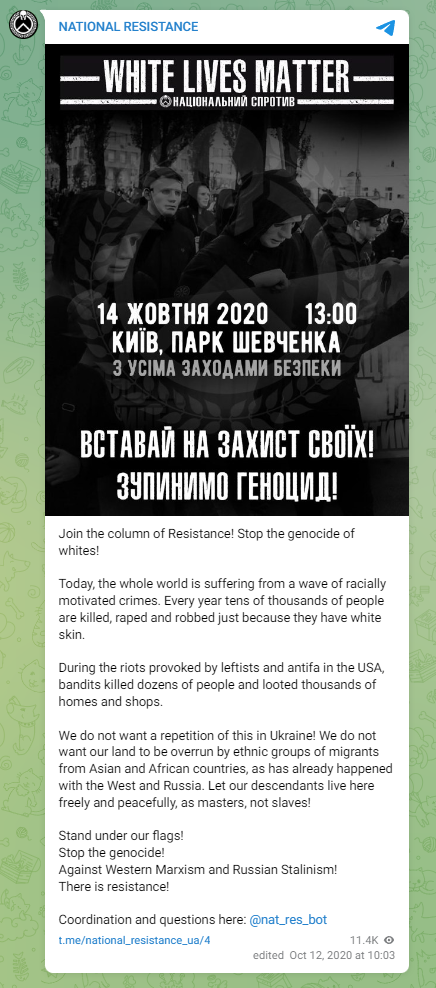

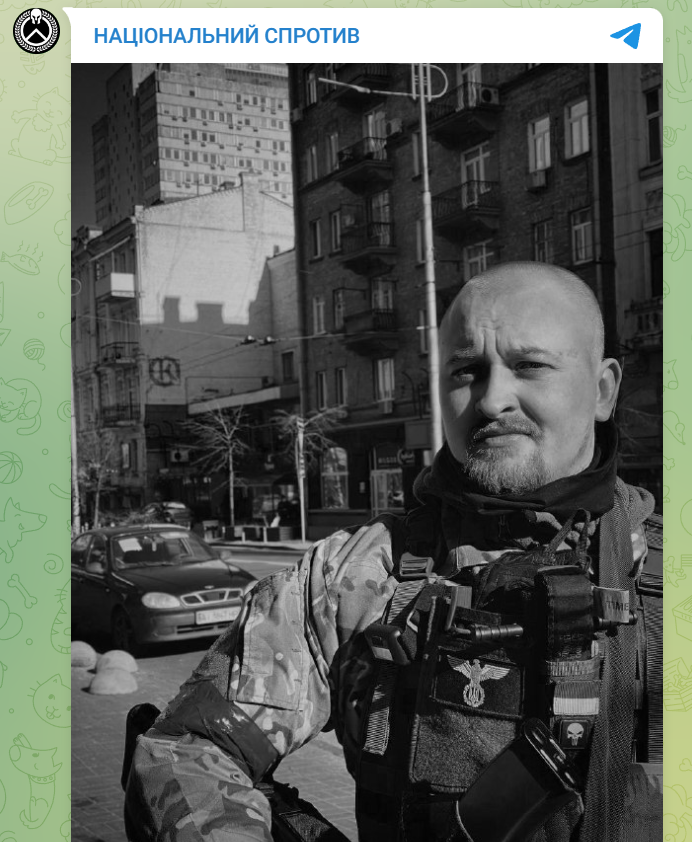

With the National Resistance he promotes a form of right-wing politics free of the “liberalism” he saw in Right Sector, National Resistance follows the ideology of “Identitarianism”, a form of European white nationalism and they’re happy to broadcast these ideas to their followers, the group’s very first Telegram post promised to protect Ukraine from a “white genocide” they said had already claimed Russia and Western Europe, with those countries apparently being “overrun” by Asians and Africans, they also like to promote propaganda honouring SS Galicia and show off various Nazi symbols, including the Black Sun, Reichsadlers, MP-40 Submachine Guns and an SS Division Patch… You know, just in case you didn’t get the memo.

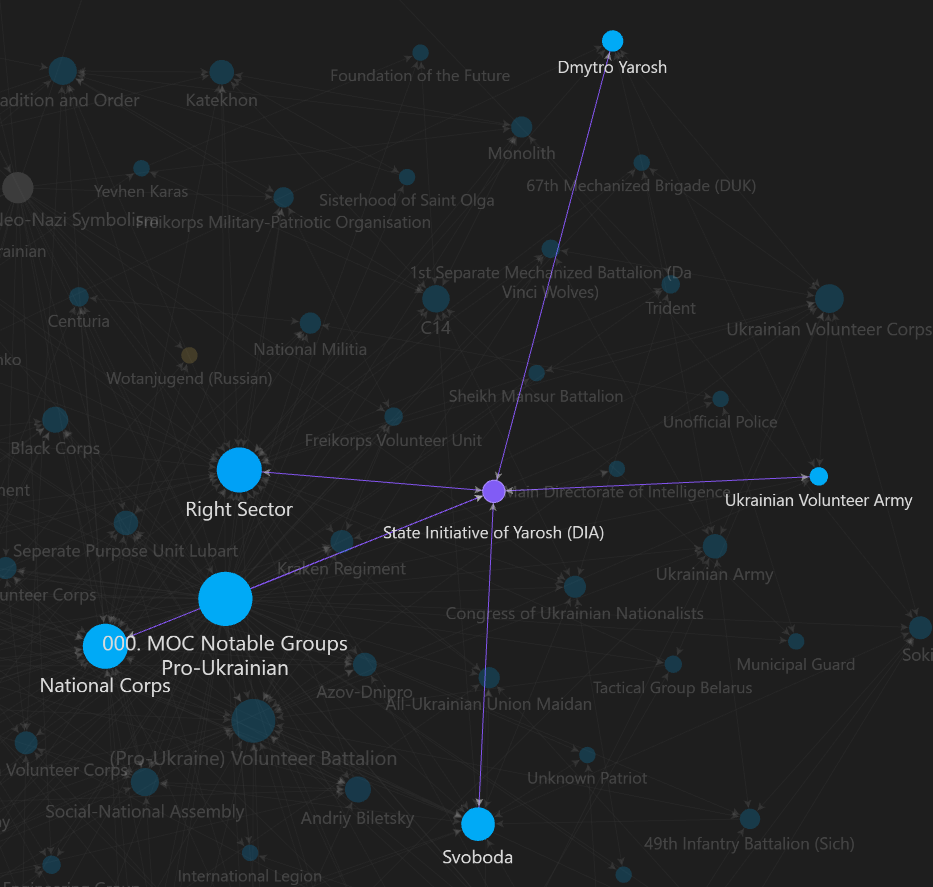

Other splinters are of a much larger calibre. One of the founders of Right Sector, the then leader of Right Sector’s Trident and the commander of the Ukrainian Volunteer Corps unit, Dmytro Yarosh, left the conglomerate in 2015, complaining that its “pseudo revolutionary activities” were threatening Ukraine’s integrity. While he claimed to be a passionate revolutionary, he believed it would be better to preserve the Ukrainian state and use it as a mechanism for implementing his political visions, claiming that “We are in opposition to the current government, but we do not consider bloody (and doomed to defeat) riots against it appropriate.”

When Yarosh left the Right Sector, around 20% of its membership went with him and formed their own organisations, to carry out political activism they formed a party known as the “State Initiative of Yarosh”, and to continue their role in the Donbas war effort they formed a militia known as the “Ukrainian Volunteer Army”.

And it’s interesting to see the differences in the reasoning behind these splinter groups, on the one hand you have Yarosh saying Right Sector is too radical, and on the other you have Svinarenko saying Right Sector is too moderate, it seems that because of the movement’s disjointed nature even its own expats can’t decipher where it really leans politically.

And of course this isn’t helped by the fact that like Svoboda and to a lesser extent National Corps, Right Sector has played the optics game, promoting themselves as more moderate to outside observers, for example back in June 2014 the group’s spokesman Artem Skoropadsky was interviewed by the Foreign Policy magazine, and he openly rejected ethno-nationalism, promoting instead a more healthy kind of nationalism, civic or cultural in nature, where anyone who wanted to be Ukrainian could be if they supported the country.

Skoropadsky essentially presented the Right Sector as a more average conservative movement, aiming to replicate a “Europe of the Polish kind”, and Foreign Policy also noted that the group had even reached out to Israel with a pledge to fight “anti semitic provocations” and “racist phenomena”. But the magazine went on to write that while Right Sector had been more careful than others, like Svoboda, the group was ultimately cut from the same cloth of far-right, ultranationalist politics.

The thing is, because Right Sector is more of a coalition than a party like Svoboda or the National Corps, it’s hard to say how much of this is propaganda and how much of it is Right Sector genuinely being less extreme than the other movements in this umbrella, for example Trident is a group that openly denounced Fascism as an enemy, yet they were willing to work alongside a blatantly Nazi group like the Social-National Assembly.

And although the Assembly later left Right Sector and disbanded, this cooperation continues, with Right Sector endorsing a joint list with Svoboda, National Corps and the Yarosh Initiative for Ukraine’s 2019 general elections, and supporting a joint candidate for that year’s Presidential elections as well, alongside Svoboda, the Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists, and another group called C14, more on them later.

So even if we assume that Right Sector isn’t as tied to Fascism or Nazism as some have claimed, they are definitely part of this web of groups, while it’s usually not fair to judge people through guilt by association, when we’re talking about a coalition of ultranationalists trying to gain political power, it seems justified in this case.

Whatever differences they may have, these groups are able to unite around common Ultranationalist sentiments, common vigilante strategies, and a common opposition to liberals, leftists, progressive agendas and compromise agreements.

Since the 2022 invasion, both the original Ukrainian Volunteer Corps and the Volunteer Army have both continued operating, but pursuing different strategies.

In late 2022, the Volunteer Corps decided to join the Ukrainian military, later being rebranded as the “67th Mechanized Brigade” of the Ukrainian Army, while the Volunteer Army has chosen to remain independent, as an unofficial paramilitary group.

But in this realm of constant multiplication and proliferation, it isn’t a surprise that we see even more splinters. Another group that broke off from the Volunteer Corps is the “DaVinci Wolves”, a unit formed by former Right Sector commander Dmitry Kotzubaylo, callsign “DaVinci”, who was reportedly was the youngest commander in the Ukrainian Military and was awarded the Hero of Ukraine honour by Volodymir Zelensky, the DaVinci Wolves are officially known as the 1st Separate Mechanized Battalion of the Ukrainian Army.

And once again these battalions with far-right connections lead to some rather embarrassing photo ops and disturbing symbolism for Ukraine.

Take a look at this image, where a member of the battalion is resting in a trench, the image was uploaded to social media by the Ukrainian Defense Ministry, but a US-based publication, the New York Times noticed something rather unnerving about it.

See that patch? It uses the SS symbol known as the Totenkopf, or “Deathshead”, a common logo of the Nazi scene. In this case, the Ukrainian Defence Ministry claimed that the use of the patch could be interpreted “ambiguously”, as the specific patch design, a Totenkopf imposed on the colours of the Ukrainian flag, was apparently a piece of merchandise from a band called Death in June, which has responded to claims of Nazism by saying that it’s “their problem” if critics take the logos they use at “face value”.

But whether the band is using the Totenkopf because of genuine Nazi sympathies or for a more subversive reason, given that the Wolves are the offspring of a far-right coalition, their use of these patches, which NYT has noted isn’t just a one time occurrence, probably isn’t so subversive.

Ambiguous or not, this is yet another example of Nazi symbolism making its way into the Ukrainian Military.

The last splinter groups we found in this mess of Right Sector affiliates are tied to a group that actually predates Right Sector entirely, earlier we mentioned that one of the Right Sector groups was called Ukrainian National Assembly - Ukrainian People’s Self-Defense or “UNA-UNSO” for short, founded in 1990.

Well, it turns out that as well as fighting under the banner of Right Sector’s Volunteer Corps, the UNA-UNSO also formed their own units in the Ukrainian military as well, creating the “55th Territorial Defence Battalion” and the “131st Separate Reconnaissance Battalion “UNSO”” to fight in Donbas; Since the 2022 invasion the 131st Battalion was renamed from “UNSO” to “Yevhen Konovalets”, named after one of the key leaders of the original Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists.

Additionally one of UNA-UNSO’s founders, Dmytro Korchinsky, formed his own party called Brotherhood all the way back in 2004, after being ousted from the group. Brotherhood is a far-right party of a particularly religious flavour, having previously described itself as the “Orthodox Taliban”, although it had nothing to do with the actual Orthodox Churches in Ukraine.

And like all of the other groups, Brotherhood also involved itself in the Ukraine conflict, initially forming a group called the “Jesus Christ Hundred”, which was attached to a unit called the Shakhtarsk Battalion, before splintering off to form the “St Mary’s Battalion”. Activists from Brotherhood continued their participation in the Donbas War until 2016, but they returned after the 2022 Russian invasion, forming a new unit called the “Brotherhood Battalion” which participated in sabotage missions inside Russia.