Previous Subchapter → 3.1 Russia’s break with the West - 1917-1980s

From the very beginning NATO was an alliance aimed at countering the Soviet Union, of which Russia was a key member; But while NATO was a clear threat to Russia, it was a threat that existed only in theory, NATO existed to fight a Third World War, and that was a war which never came to pass.

In terms of Russia’s anxiety towards the west politically, their Cold War fears were simple enough to explain, the USSR which Russia was part of was Communist and a superpower, the West was Anti Communist and a rival superpower, but what about after the Cold War, when Russia became its own nation?

Well, the Western nations are well remembered for their support of the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, whose actions led to the end of the Cold War and the formation of the Russian Federation, but Russians think about these events very differently to how Westerners do.

Gorbachev’s term as leader of the USSR was marked by 3 main policies, Perestroika, Glasnost and the “Sinatra Doctrine”:

-

Perestroika involved a restructuring of the Soviet economy from a planned model to a market one

-

Glasnost, the loosening of political restrictions on Soviet society, especially regarding the media and speech

-

And the ”Sinatra Doctrine”, a complete overhaul of Soviet foreign policy, a switch from an interventionist stance known as the Brezhnev Doctrine (where Eastern Bloc states would be kept in the Soviet orbit and maintain Soviet style political systems no matter what) to a non-interventionist stance where Soviet troops would be withdrawn from Eastern Bloc nations and their people would be given the freedom to choose for themselves between Communist Party rule and Western style representative rule.

In the West, all of these policies were viewed highly positively, and this led to an unprecedented warming of relations between Western nations and the USSR, they represented a shift towards freedom, Gorbachev was regarded as a kind of architect of liberty, but in the Soviet Union itself, they proved far more divisive.

Perestroika was intended to drag the Soviet economy out of stagnation, and promote growth, instead it resulted in the exact opposite trend, the Soviet economy spiralled into decline.

While Glasnost was more of a success, creating possibly Russia’s freest era in recent memory, it also opened the floodgates of ethnic tensions as boundary and status disputes surrounding the Soviet Republics, issues which had previously been kept quiet by Soviet censorship, began to be voiced openly, several autonomous regions of the Republics, in particular the regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia in Georgia and Chechnya in Russia, sought to become Republics in their own right, still part of the USSR, but independent from their home countries.

Despite not even having autonomy, the Transnistria region of Moldova then also declared independence after holding a referendum, sparking a war between Transnistrian rebels and the Moldovans, constitutional and ethnic conflicts were breaking out throughout the USSR.

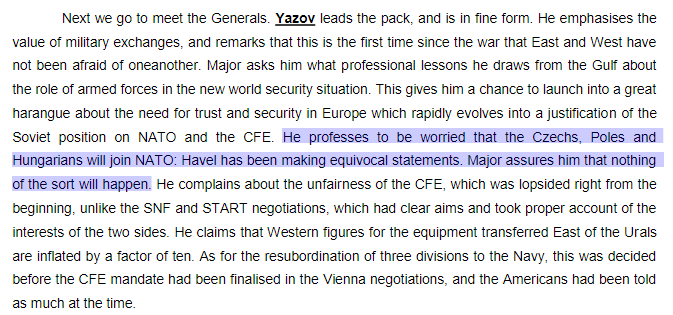

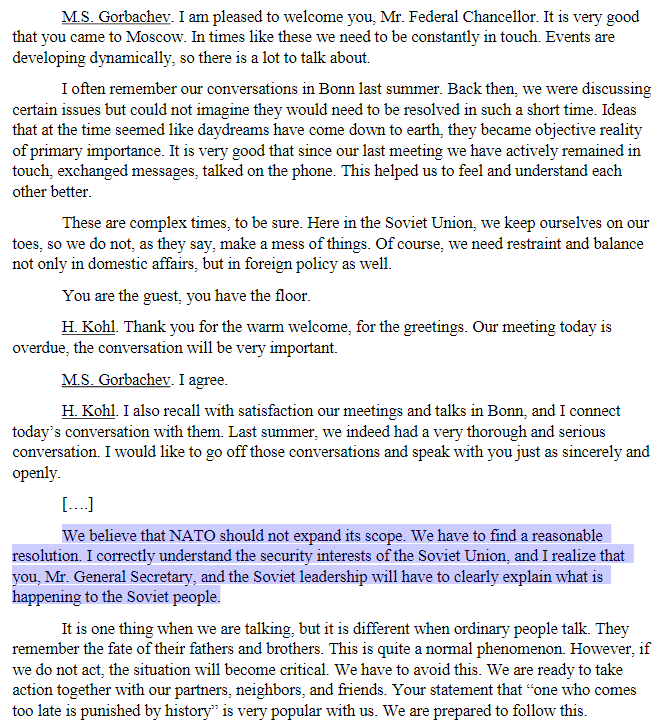

And lastly the Sinatra Doctrine lead to major anxieties among Soviet leaders that the disintegration of the Eastern Bloc could give way to major security problems for the USSR, figures like Dmitry Yazov, the Minister of Defence and even Gorbachev himself expressed fears that Eastern Bloc countries breaking from the Soviet orbit could seek to join NATO in conversations with Western leaders like British Prime Minister John Major and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl.

While these leaders assured the Soviets at the time that NATO expansion wasn’t on the cards, the security, economic and ethnic tensions in the USSR reached their breaking point and in August 1991 Yazov along with other figures like KGB leader Vladimir Kryuchkov, led a coup to overthrow Gorbachev, the coup failed but these events killed off the legitimacy the Soviet Union had left, and Gorbachev ended up having to take a back seat to his political rival, Russian President Boris Yeltsin.

While Gorbachev is remembered poorly, Yeltsin did far more damage. Yeltsin was the man who finally pulled the trigger on the USSR as he together with the leaders of Ukraine and Belarus signed Belovezh Accords which, although legally disputed, practically brought the Union to an end.

Attribution: RIA Novosti archive, image #848095 / U. Ivanov / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Attribution: RIA Novosti archive, image #848095 / U. Ivanov / CC-BY-SA 3.0

As leader of the newly independent Russia, Yeltsin caused even more havoc than Gorbachev, unlike Gorbachev who wanted to preserve the Soviet structure by reforming it, Yeltsin wanted to destroy it outright by any means necessary. He did this by rapidly forcing through reforms much more extreme than Gorbachev’s Perestroika, switching the economy from state pricing to market pricing right after taking power, even though the market had barely even been created and was still adjusting from the Soviet management style (based on bureaucratic planning) to a private management style (based on profit earnings).

The result of this was an inflation rate of crackpot proportions, over 2000% in 1992, and roughly 800% in 1993, and unemployment, which was nearly non-existent in the Soviet era, rose through the decade of the 1990s, reaching over 10% of the whole population, around 14 million people, by the decade’s end; The new Russia began its life in a death spiral.

Throughout this process, Western governments continued to support Yeltsin as he dragged Russia to its knees, offering Yeltsin over a billion dollars in aid to push through the reforms.

Just for comparison, so you can see just how bad those inflation numbers were, the inflation rate of modern day Russia, even under sanctions and in the middle of a major war, reached a high of around 17%, with unemployment at about 5%.

The reaction to these reforms was massively split in Russian society, with some being horrified by the country’s economic collapse and others hopeful that the end result would make the suffering worthwhile, the Russian Parliament (the Supreme Soviet) was in the first camp of this split, and pushed against Yeltsin, attempting to block further reforms, after a referendum in April 1993 failed to resolve the dispute between Yeltsin and the parliament, he dissolved it in September 1993, even though constitutionally he didn’t have the power to do so.

The parliament refused to dissolve and retaliated by impeaching Yeltsin, leading to a standoff resembling a civil war, as the streets turned to mayhem both sides appealed for military intervention, in early October the Russian Army decided to side with Yeltsin and bombed the parliament building with tanks, forcing the parliamentarians to surrender.

A new parliament, the Federal Assembly, was then formed by Yeltsin in December 1993, along with a new constitution which gave much more power to the Russian presidency at the expense of the parliament.

Following this brutal episode, where elected politicians had been silenced with tanks, the “leaders of the free world” of course supported…

Yes, that’s right, Yeltsin. Western governments blamed all of the violence from 1993 on Yeltsin’s opponents and hailed him as a democratic reformist, despite the fact that his reforms created mass poverty and turned Russia from an emerging democracy with some separation of powers towards an authoritarian system with power truly in the hands of one person, the President.

The end result of this process was a system where a select few elites (mostly former influential bureaucrats and gangsters associated with organised crime) swallowed up the property previously owned by the Soviet state while shutting the Russian people out of the picture; These elites then used all of their acquisitions to create massive financial empires, with control over not just the financial sectors, but also the media, in the West we usually dub these elites the “oligarchs”, and we don’t have much love for them in the modern day.

The combination of Yeltsin’s constitutional changes and the disproportionate influence of the oligarchy essentially concentrated power into the hands of a very small minority, stifling the Russian democratic process just as it was emerging.

As this massive internal crisis in Russia was unfolding, there were 2 big international issues for Russia, NATO expanding its military role and the Post-Soviet wars.

To sum up the Post-Soviet Wars, when the 15 new countries came about from the ashes of the USSR, there were populations that didn’t want to be part of them and were willing to fight to do so, the 3 main flashpoints of these for Russia were the regions of Transnistria, South Ossetia and Abkhazia.

Following the Soviet collapse, the war between Moldova and the Transnistrian separatists continued, Moldova became its own country with Transnistria internationally recognised as one of its territories, but the separatists had already established themselves by this point as a breakaway state, renaming Soviet Transnistria into the “Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic” or more simply, Transnistria.

The conflict ended in 1992 with a Russian intervention, Russian troops acted as peacekeepers and forced the Moldovans into a ceasefire.

To this day Transnistria is its own country, but recognised by the international community as part of Moldova.

The South Ossetia and Abkhazia Wars followed a similar pattern, after a period of fighting between the Georgian military and the two separatist factions Russia intervened on behalf of the separatists and South Ossetia and Abkhazia became their own countries, though still recognised internationally as part of Georgia.

While these Post-Soviet conflicts were taking place, NATO became a major concern, Russia had already expressed opposition to NATO, with Yeltsin adopting his predecessors opposition to NATO expansion, but this concern grew as the organisation began acting further afield, in the 9 years after the end of the USSR NATO conducted 10 different military operations, the first in the organisation’s history, all taking place outside NATO borders.

These 10 operations involved interventions in a foreign conflict called the Yugoslav Wars, a series of conflicts in steadily disintegrating Yugoslavia, a nation which was facing insurgencies from multiple members of its union trying to gain independence, and several other wars between ex-members that already had.

Yugoslavia was another case of a multi-national diverse country collapsing into ethno-nationalist conflict, like the past collapses of Austria-Hungary, the Russian Empire or the USSR, but on a slightly smaller scale.

9 of NATO’s operations involved Bosnia and Herzegovina, an autonomous province of Yugoslavia that gained independence and immediately collapsed into a war between 3 groups, Bosniaks, Croats and Serbs, many of the Serbs had rejected independence from Yugoslavia and formed a seperatist state inside it known as “Republika Srpska”, fighting bitterly with the Croats and Bosniaks.

The first 6 operations resolved this dispute by blockading Yugoslavia, enforcing sanctions against the region and carrying out airstrikes against the Serb forces in Bosnia, pressuring the warring parties to come to a deal in 1995 called the Dayton Accords.

In these Accords, the Serbs agreed that Serb territories of Bosnia would become part of Republika Srpska, Croat and Bosniak territories would become part of a territory called the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the 2 territories would unite as one country called Bosnia and Herzegovina, separate from Yugoslavia, the remaining 3 NATO operations in Bosnia involved enforcing this agreement.

The last of NATO’s Yugoslav operations involved another territory, Kosovo, a conflict which will be discussed on more detail in the final episode of this series, for now what you need to know is that Kosovo was, at the time, a region of Serbia, a member state of Yugoslavia, in this last NATO operation, NATO forces bombed Yugoslavia, forcing Yugoslav forces to retreat from Kosovo and allowing Kosovo to split from Serbia to become its own country.

In short, at the end of the Cold War the Russians were essentially watching in real time as their old enemy changed from a defensive alliance to an offensive one, creating entirely new countries through their interventions in the space of only a few years after the collapse of the USSR, and they were powerless to do anything about it.

These episodes essentially reignited the tension between Russia and NATO that was supposed to have been buried after the Soviet era, driving a wedge between Yeltsin and his Western allies, but that alliance still prevailed as a product of mutual interest: The West wanted Yeltsin to stay in power, and so did he.

In 1995 when Yeltsin’s popularity was in the gutter, he received US support in aid of his bid to be re-elected in 1996, an election he narrowly won. US President Bill Clinton agreed to slow the process of NATO enlargement, and speed up the delivery of a major loan to Russia from the IMF to boost Yeltsin’s election prospects, on top of this a US organisation known as the IRI (or “International Republican Institute”) offered training to activists in Russia, this was known as “democracy promotion”:

- Thomas Graham (Chief Political Analyst at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, 1994-1997)

So essentially, the Clinton administration was, consciously or not, placing their insistence that the Russians embrace Capitalism above the process of turning Russia into a real democracy, and they lied to themselves by pretending the two were the same thing, even as the undemocratic nature of the new Russian establishment, headed by the politicians and oligarchs, was becoming more and more clear.

But while Yeltsin and Clinton seemed to have a mutual understanding on Russia’s direction, they didn’t agree on Europe’s, and after Yeltsin’s re-election those tensions were dragged up again. In October 1996, 3 months after Yeltsin had been returned to power, Clinton returned to the topic of NATO expansion, calling for the first ex-Eastern Bloc countries to join the alliance by 1999, and insisting that Russia would not get a veto on the matter. Clinton got his wish, with Czechia, Poland and Hungary joining in 1999, a year that was closed out by Yeltsin’s resignation as President, passing the problem of NATO on to his successor, Vladimir Putin.