Previous Subchapter → 1.5 History - Goodbye USSR

Fast forward to 2010 and Ukraine has elected its 4th president, Viktor Yanukovych. Yanukovych was a politician that viewed Ukraine as a neutral power, one which should remain close to both the West and Russia and shouldn’t join either’s military alliances, in an attempt to balance the country’s fragile sects, he also aimed to bring Russian speakers together with Ukrainian speakers by recognising Russian as a second official language alongside Ukrainian, passing a law to make minority languages official after 2 years in office.

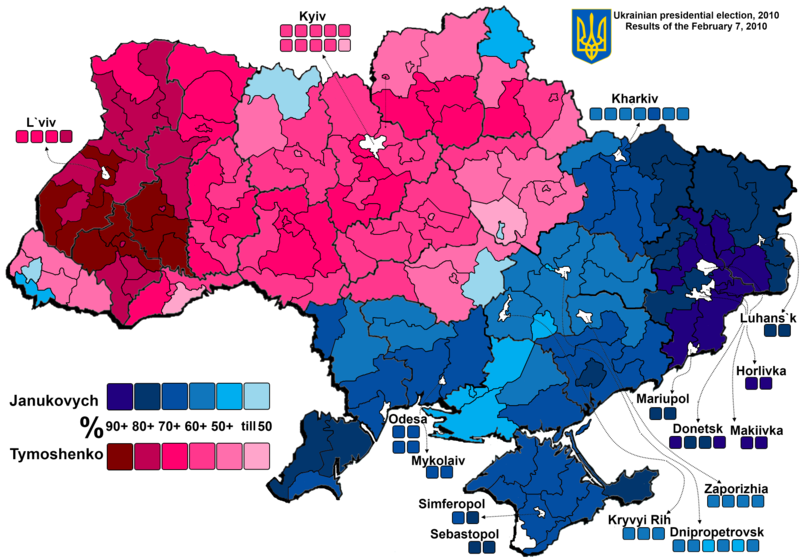

But Yanukovych was in a shaky position from the start, having narrowly been elected on only a 3% lead over his rival Yulia Tymoshenko, with the West of the country overwhelmingly rejecting him and the East overwhelmingly supporting him.

Author: Vasyl Babych Licence: CC-BY 3.0

Author: Vasyl Babych Licence: CC-BY 3.0

And where Ukraine’s divide truly tore Yanukovych apart was the issue of membership of the European Union, where there wasn’t much room for neutrality: EU membership was a policy with strong support in Ukraine’s West but much weaker support in its East, one camp wanted it and the other camp didn’t, damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

Throughout his presidency Yanukovych had pledged to support membership with the EU, but in late 2013, following pressure from Russia to back away Yanukovych refused to sign an Association Agreement that would’ve brought Ukraine one step closer to EU membership, and his party rejected a number of reforms that the EU demanded as a condition for joining, essentially sabotaging their own application process.

This sparked outrage among Pro Western elements of Ukrainian society and led to the formation of the Euromaidan, a protest movement that demanded a return to plans for EU membership and the resignation of Yanukovych and his government, Pro Russian elements of Ukraine responded with a counter movement, the Anti Maidan, in opposition to the protests, large opposing forces born from Ukraine’s long running political divisions.

To quote from The Washington Post again:

“The mass protests, and thus most foreign journalists, are in the capital city of Kiev. […] But President Yanukovych is from the eastern, more Russian part of the country, where he served as a regional governor for several years. In 2010, 74.7 percent of Kievans voted for Yanukovych’s opponent; it’s not shocking that they would want him to leave office.